Toppy, Tilley and the Faithful Jerry: decadence on display in the performing lives of the 5th Marquis of Anglesey (1875-1905)

A Staging Decadence Long Read

Guest post: Professor Emerita Viv Gardner,

University of Manchester

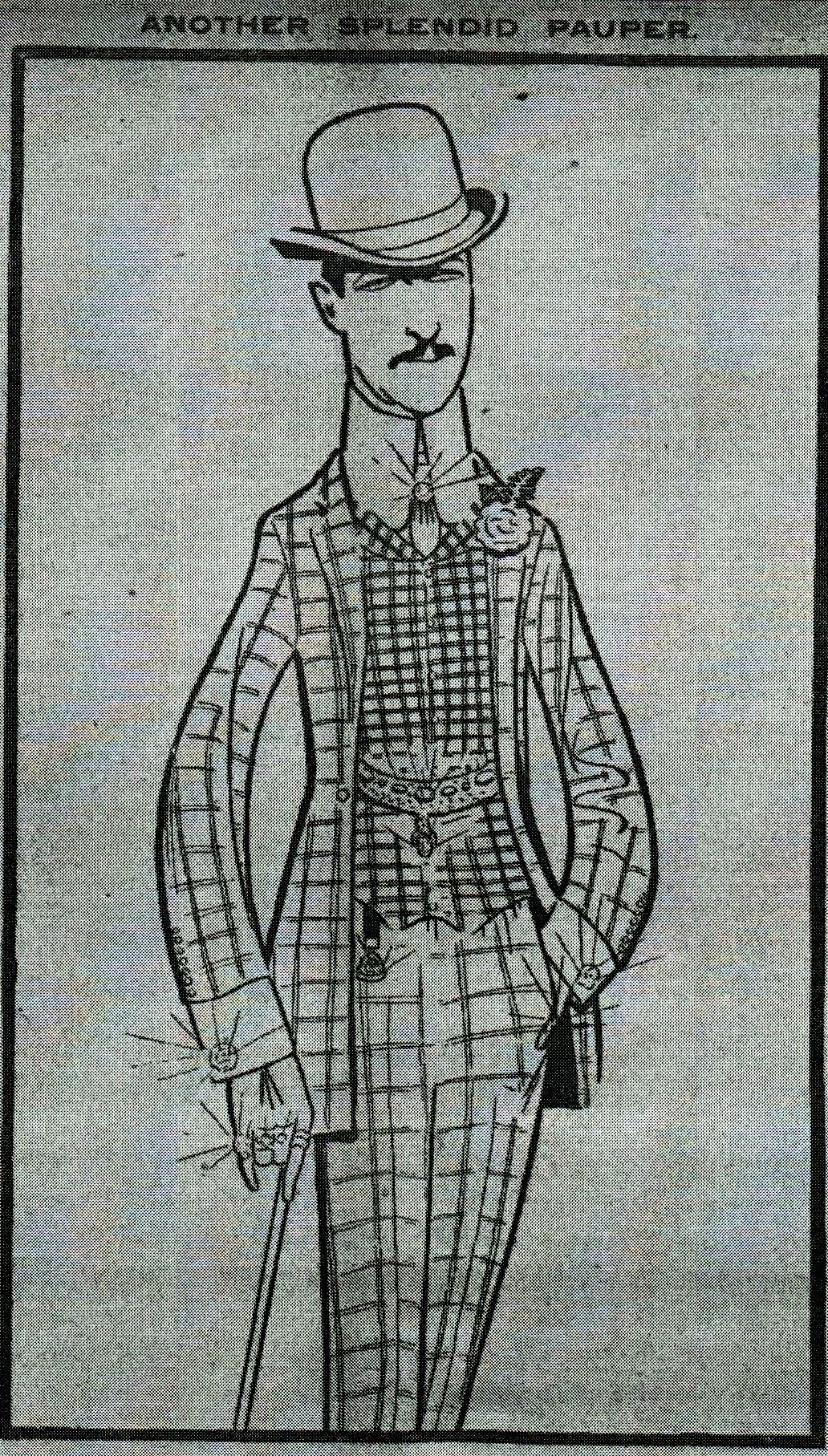

Fig. 1: Daily Mirror, 4 June 1904, p. 7.

‘He wore a ten-pound orchid in his coat,

La-di-da.

And a thousand guinea necklace round his throat,

La-di-da.

In his teeth a golden pick,

In his hand a jewelled stick,

And a million in his pocket, la-di-da, la-di, da,

But not long in his pockets, la-di-da.’

This parody of a popular song was sung by ‘a well-known actor’ on an unnamed stage as details of the 5th Marquis of Anglesey’s disastrous financial affairs emerged in July 1904.[1] It wasn’t the only stage satire of the ‘Splendid Pauper’ in his brief life; he even featured in the Westminster School performance of Terence’s Andria, where ‘Lord Anglesey’ was one of the ‘modern topics … ingeniously applied’ to the ancient comedy.[2]

Decadent or decadent?

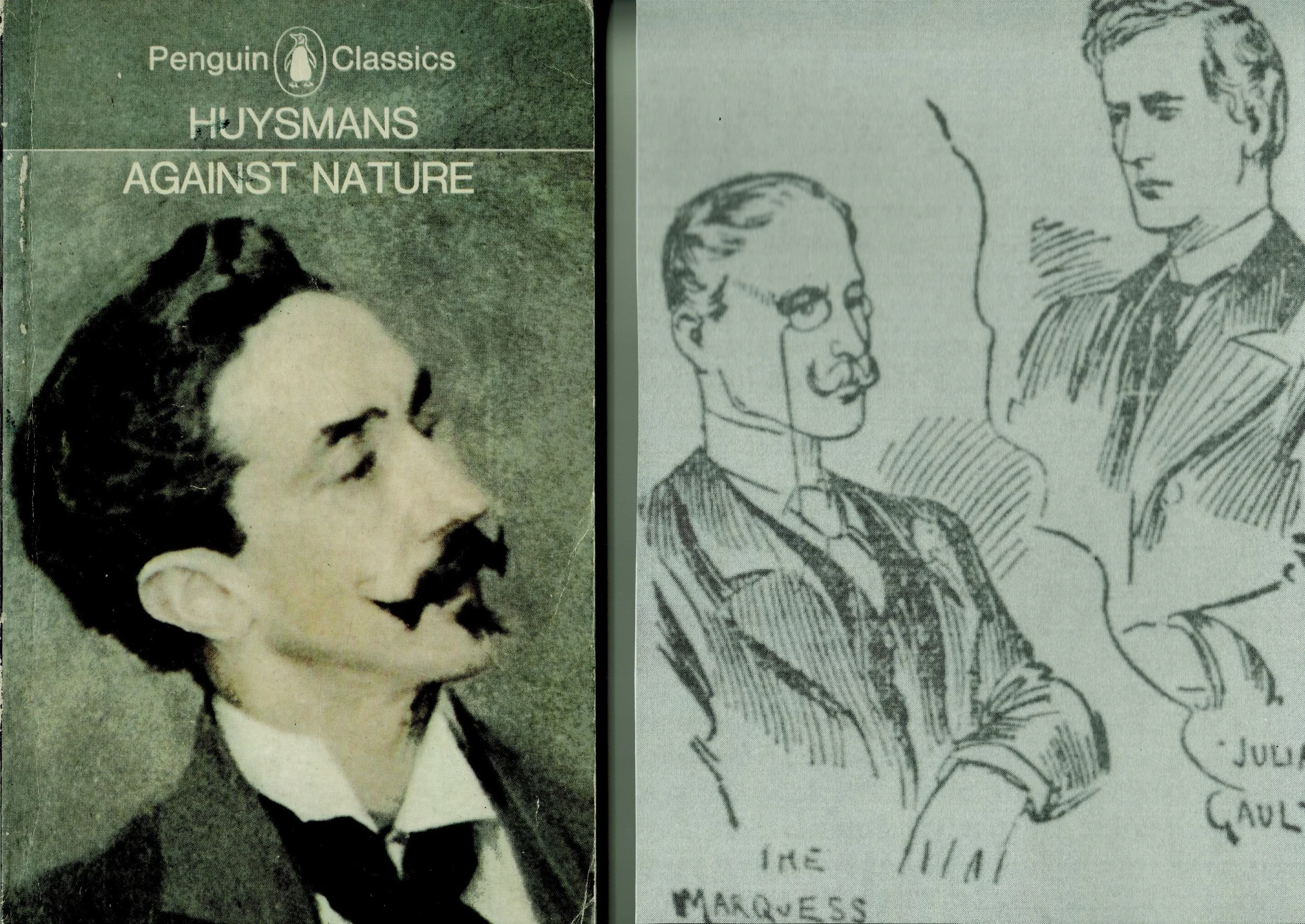

This blog post has had many titles. The latest include ‘Decadent (or) Dickhead?’ – reflecting my ambivalent relationship with my subject – and, the more grown-up version, ‘Decadent or Phallic Narcissist’. [3] There seems little doubt that he was ‘decadent’; many newspapers used this term about him both during his lifetime and in obituaries. Whether he was a Decadent, or thought himself a Decadent, or part of the aesthetic movement which at times intersected with Decadence, and spanned the fin de siècle and his lifetime, is less easy to determine. This has raised a number of questions for me. Does decadence mean Decadent? Can one be an innocent or accidental Decadent? Or even an amateur Decadent? Does Decadence adhere to the eccentric? Does the fact that one shared moustaches with Robert de Montesquiou,

Fig. 2: Left – Portrait of Robert de Montesquiou by Baldini. Author’s own copy of the Penguin Classics cover of J. K. Huysmans, Against Nature (1959). Right – newspaper sketch of the Marquis of Anglesey in court. Tamworth Herald, 21 September 1901, p. 6. British Newspaper Archive.

who, coincidentally, lived near one’s step-mother in Versailles[4] and may even have been present at her radical aesthetic salons (with Natalie Barney, Romaine Brooks, Elsie de Wolfe and Bessie Marbury), qualify one as an Aesthete and/or Decadent? Or that one perfumed one’s programmes with patchouli (reputedly) and one’s car exhaust (again reputedly); [5] or that one preferred artificial, and artificially-scented, flowers to Nature’s own. Does a taste for the popular – or purple underpants, uniforms (especially designed), and strangely manicured nails – exclude one from, or include one with, the Decadents?

Fig. 3: The Marquis of Anglesey’s underwear. National Museum of Scotland. (https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/collection-search-results/underpants-mans/350736). ©

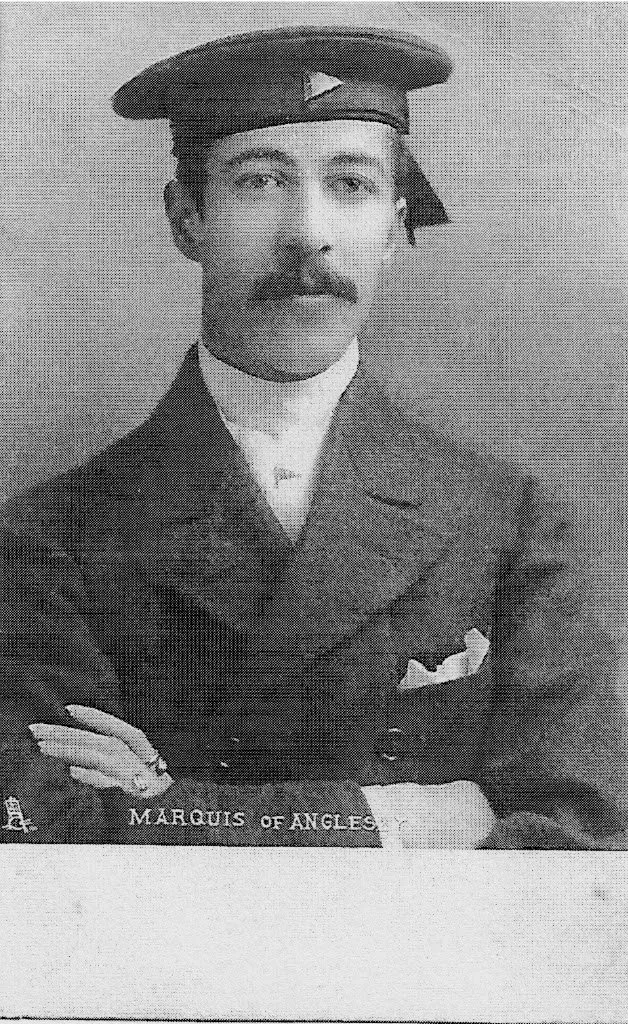

Fig. 4: Postcard of the 5th Marquis in naval uniform with pointy nails. Courtesy of John Cowell.

Clough Williams Ellis of Port Merion fame described the 5th Marquis of Anglesey as ‘reminding one of an Aubrey Beardsley illustration come to life’, as ’a sort of apparition … quite unforgettable – a tall, elegant and bejewelled creature, with wavering elegant gestures’.[6] This is the only link I have found to either the British or French Decadents. When the 5th Marquis’s library was sold in 1904, there were no signs of Huysmans’s À Rebours (1884), or copies of The Yellow Book or even Wilde’s works – though these might have been removed to protect his reputation – rather Ouida, Mary Braddon and numerous, un-named French novels. Throughout his house, however, were very large, photographic portraits of himself in costume. The Marquis did aspire to an aesthetic career; as well as creating his own needlepoint, in December 1899 he danced as a ‘lighting-change artist’ on the stage of the Central Theater in Dresden, and in late 1901, he ‘stole’ a professional theatre company and performed with them until his money ran out and insolvency proceedings were instituted in 1904.

Fig. 5: The Marquis as Pierre Rougon in Voices of the Night, 1903. Photograph: John Wickens. The Sketch, 22 March 1905, p. 325. British Newspaper Archive.

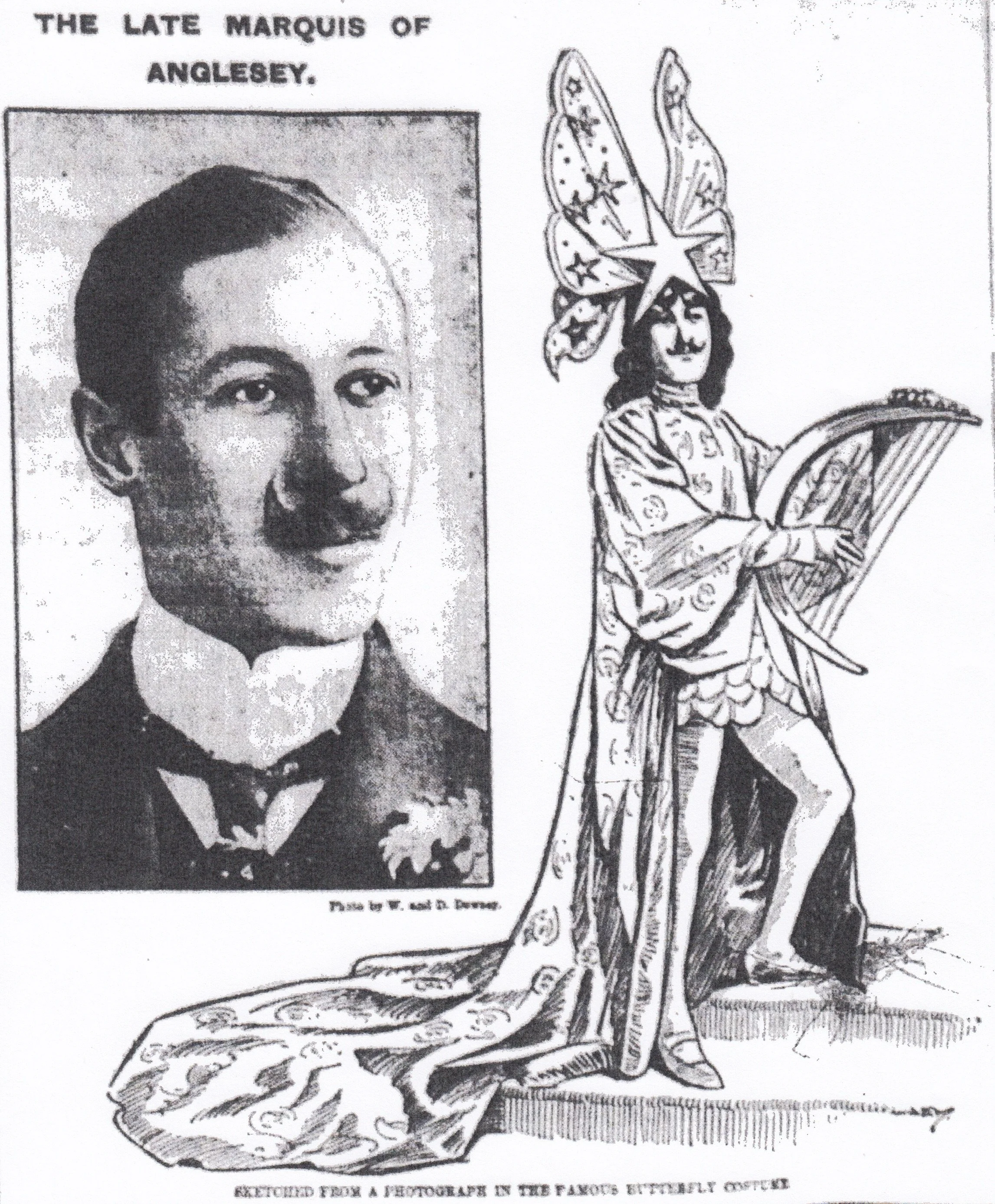

His repertoire was, apart from his final appearance as Lord Goring in Wilde’s An Ideal Husband (1895), gloriously popular. His reputation as a performer was built on his two pantomimes, Aladdin (1901-02) and Red Riding Hood (1902-03), musical and society comedies, and, above all, his Loïe Fuller-inspired dances, earning him the sobriquet ‘The Dancing Marquis’. He even wrote four short dramas for the company in which he starred as a drunken father, a murderous convict (wearing a costume lined with silk), an accidental matricide (you can find a transcription of this particular play below), and a ‘beater of women’. These all have traces of Zola’s ‘social modernity’, but are more Grand Guignol or melodrama than Remy de Gourmont or Jean Lorrain. From the outside, the 5th Marquis was indeed ‘a decadent’, but in other ways he does not fit the movement as we understand it. He was not a writer despite his four plays, which were adaptations of other plays or popular novels. He was not a Decadent in the manner of Wilde or Beardsley. His serpentine dancing was more pantomimic

Fig. 6: The Marquis in his Butterfly Dance costume. Daily Dispatch, 15 March 1905, p. 7. British Newspaper Archive.

than the Art Nouveau-inspiring Fuller. If the Decadent milieu was urban and its centre was Paris – he did have an apartment off the Champs Élysées and his somewhat rackety maternal family lived nearby – he is invisible in all the known circles of aesthetes and radicals, including his own step-mother’s. Nor was he ‘well known in London. … for he was too bizarre a person to fit on with conventions of society’,[7] and only came to public notice when his behaviour attracted interest, often in the form of ridicule, from the popular press – trailing back to his hotel in the rain, mocked by urchins, after the coronation of Edward VII, or robbed of his jewellery by his French valet while he is at the theatre watching William Gillette in Sherlock Holmes, the coincidence offering a gift for sensation-hungry journalists.[8] His centre was on a culturally remote (to Society) island off the north coast of Wales, Anglesey; his circle, family and household, his audience, ‘local tradesmen and their wives’.[9]

Fig. 7: The Marquis (centre) in ’Byzantian’ fancy dress (with lily) amongst his family, friends, and staff (including his chauffeur as Charles I, actor Frank Hilton as ‘the daintiest of Polchinelle dolls’, and his house manager, Walter Player, in coronation robes). 27th birthday celebration, June 1902. Author's own collection.

Plas Newydd, or Anglesey Castle, as the Marquis renamed the house in 1902, became his stage, both literally – he converted the existing music-room-with-stage, which had been constructed in the house’s chapel, into a ‘bijou’ blue and sunflower-themed theatre, which he named the Gaiety, after Sarah Bernhardt’s theatre in Paris – and existentially. Here and among the local community, he indulged his fantasies of both self and performer.

The electric lights were switched off; for a time darkness reigned supreme. In a few minutes the drop-scene re-ascended, showing us the Marquis [as Prince Pekoe in Aladdin] garbed, Crusader fashion, in a close-fitting suit of sequin-mail. No ordinary headgear his, but one of pearls; diamonds hung round his neck and seemingly blazed from every portion of his person where a gem could be conveniently hung. ... From his arms hung a delicate sheemy [sic] silk, with which he was to make his butterfly-spidery motions. Standing in the middle of the stage in the confused medley of kaleidoscope lights, skilfully handled by the limelights man, he presented a most unaristocratic appearance. As a stage hybrid descendant of some erstwhile Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ay-ite he was an unqualified success; as a representative of the English aristocracy -------- ! But he caught on. Our motley audience cheered him to the echo in Welsh and English. A second turn was demanded and given. A third was asked, but this time the Marquis cried, ‘Enough!’ and gave us instead a stage bow, composed two parts Beau Brummel and one part of the curtsey of the blushing country damsel… and so the strange performance ended, and the curtain finally fell on the tall, spare, sallow youth. [10]

As both Pekoe and Boy Blue, he wore costumes which were of such ‘indescribable magnificence’[11] that they ‘almost baffle[d] description’.[12] In Aladdin he had at least six costumes, and for Red Riding Hood he was said to have ‘obtained a score or so of specially designed costumes of extraordinary splendour, costing in the aggregate of about £500, and these he [had] worn in turn during the run of the pantomime’.[13] It is not clear whether he rotated costumes as Boy Blue or wore all twenty in one performance, but one of his fellow actors in Aladdin wrote in her diary about how, ‘Lord A wore a glorious costume … like moonlight’, adding ‘He wears different costumes every night’.[14] What attracted most attention was the ‘quarter of a million [pounds] worth of diamonds, rubies, emeralds turquoises and other rare and precious stones’ he wore as Pekoe, with a costume for the finale which was reportedly ‘almost entirely composed of diamonds’,[15] and as Boy Blue, where ‘scarcely an inch [of his drapery was] not covered in costly jewels’.[16]

Fig. 8: The Marquis as 'Boy Blue' in Red Riding Hood. The Sketch, 21 January 1903, p. 3. British Newspaper Archive.

His clothes were equally fantastic. The insolvency sales revealed items of ‘infinite splendour’ – including six Tam o’Shanters, fifteen pairs of lavender gloves, and at least 35 bejewelled walking sticks – and a wild range of coloured and patterned clothing. The 806 lots (most including more than one item, and many unworn) ranged from ‘smoking suits’ which the Lichfield Mercury described as ‘morbidly fantastic’ – including one of ‘great squares of blue and red and green [to] appalling effect’ – to a ‘lounge suit of ermine’, which would have suited ‘Dan Leno for the next pantomime’, a ‘beautiful white cloth kilt, with foxhead sporran … calculated to astonish the Highlands’, and the Marquis’s favourite dressing gown – of hundreds – a ‘dream’ in ‘heliotrope silk lined with fur’.[17] The Washington Post, more positively, found that the Marquis’s ‘choice of apparel was governed by much taste’, and that it was ‘impossible to look at the piles of embroidered waistcoats, the prismatic hues of the silken dressing gowns, the delicate variations of colour in the silken underwear …. without recognising that here was a man who thought out his own colour schemes for his personal decoration, and devoted as much time to every phase of it as Beau Brummell’.[18]

This obsession with ‘prismatic hues’ in clothing and jewellery – both real gemstones and paste, he did not seem to discriminate – was one of the signs to his critics, not only of his extravagance but his ‘effeminacy’. His challenge to sex and gender binaries in performance, however, was subtler than simply display. He was much given to ‘gender inversion’ in his performances where he played, or planned to play, well-known female roles as male. In his two pantomimes, he played ‘the kind of part which in pantomime circles is technically known as “second [principal] boy,” and is usually played by a highly attractive young lady with not very much to do except to look pretty’, not a man and peer of the realm.[19] In Dresden at the Central Theater, the Marquis called himself ‘San Toi’, from the popular 1899 musical comedy of that name, where the ‘heroine’ is a girl raised as a boy from childhood who only at the end reverts to her ‘true’ sex to marry her male lover.[20] In the pantomime, La Poupée (1900), the marquis played the female role as male; in a proposed reworking of The Second Mrs Tanqueray (1892),[21] Paula, the fallen woman, becomes the fallen man; and in A Runaway Boy, the Marquis’s adaptation of Seymour Hicks and Harry Nichols’s 1898 musical comedy, A Runaway Girl, the runaway girl, Winifred, became the runaway boy, Guy. In all these instances, he could have played the male lead, and although none of the pieces involved cross-dress, all the roles would have been known to his audience as originally female, and retained a ‘female’ romantic story line of flight from a tyrannical family member, pursuit and the triumph of true love.

Fig. 9: The Marquis as Guy Dudley (second right) in his musical brigand costume, in the 1900 amateur production of A Runaway Boy. Tatler, No. 6, 7 August 1901, p. 285. Author’s own collection.

If this destabilising of gender and sexuality was unsettling to his bourgeois audience (both in the theatre and to readers of newspapers), it also clearly gave them pleasure. His performances themselves – which were free to all comers, as were the postcards of himself in costume given away at his shows – and the various accounts of his performances and life, were immensely popular. There was, evidently, something intoxicating in his intoxication with himself, something ‘strange, abnormal’, and perhaps ‘unhealthy’ to borrow George Moore’s phrase,[22] in which, in the protected space of his estate, and above all in his theatre, both performer and spectator could immerse themselves. The inversion and destabilising was not only of gender, but of class. This was Lord Anglesey, grandson of the hero of Waterloo, cavorting on the stage in ‘unaristocratic’, less-than heroic, roles. His failure to fulfil his duty to produce an heir – or even to consummate his marriage to his cousin-wife, which would have been inferred from the terms of their separation – was further evidence to many of degeneration amongst the decadent aristocracy.

When the inevitable collapse came in early 1904 as the Marquis’s debts reached over £544,000,[23] the very things which his audiences, in the widest sense, had loved, were used to mock him, and the Marquis was put on display in various ways, including forms of performance. Vesta Tilley, the great male impersonator, bought dozens of the Marquis’s approximately 247 embroidered waistcoats at the sales, including one she wore to sing ‘Gentleman Johnny with the little glass eye’. When she performed wearing the 5th Marquis’s waistcoat – ‘a vest of delicately flowered silk’ – in front of the ‘dudes of Broadway’[24] and other spectators, they knew the origin of the waistcoat (she had told the newspapers on arrival in New York). Tilley was impersonating not just a recognisable type, the decadent dandy,[25] but an individual, the Marquis of Anglesey, as androgyne, a degenerate, neither truly male nor female. The song ‘Gentleman Johnny’ ends with the women laughing at the masher, ‘Algie’, and calling him ‘behind the scenes’ a ‘jay’ or ‘idiot’. Tilley was speaking here to and for ‘the crowd’, the mass.

Tilley, the ‘well-known actor’, and the Westminster School boys, were not alone. The mockery had started at the sales themselves. (The spectators for this performance were many of those who had been guests in his theatre and fancy dress balls, including the auctioneer, William Dew, and his family). Nowhere was this clearer than in the accounts of the sale of his clothes and costumes. On the three days when his clothing was sold, a ‘large marquee’ was erected and ‘elevated plank walks ran round the sides and down the middle. Mr Dew’s men were kept busy “walking the plank” in order to display the garments’.[26]

Fig. 10: Photograph taken in the auction-marquee Anglesey Castle sale, August 1904, showing ‘the plank’ stage and possibly ‘faithful Jerry’. General Collection of Bangor Manuscripts/25950. Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University.

When the Marquis’s clothing was brought in,

Jerry, the auctioneer’s man, was in high feather. He had to put on everything, just to show the laughing ladies and gentlemen what they look like. At one moment he was robed in a wonderful Beau Brummell tight-waisted, full-skirted overcoat of a delicate green shade. The next he was skipping about in a short cream confection which did not reach his waist. Then he appeared in enveloped in a sweet silk ermine rug, lined with pink satin. ‘You look like a bally Sulan Sultan!’ cried the auctioneer, and so well did Jerry carry his fine feathers that the rug (whose ermine was imitation) fetched £7.[27]

The Marquis was on display, but the ‘star’ of the show was ‘faithful’ Jerry. This was all done for ‘the entertainment of the laughing ladies and gentlemen’, and

When things were getting a bit slack, Mr. Dew worked up the crowd, whispering ‘the word “Pyjamas,” – and the next moment Jerry staggered into the tent under a load of the most startling creations ever seen. Nocturnes in peacock blue shot with crimson suggested the wildest freaks of Whistler. ‘Put ‘em on, Jerry!’ cried the crowd. …

More followed: ‘A specially gorgeous smoking jacket appeared on the auctioneer’s man, about his rough tweed trousers and heavy nailed boots. … ‘Fancy that,’ [Mr Dew] cried, ‘with the Broseley clay and a tankard of beer by your side’. Tweed trousers, boots, beer, and a pipe under a gorgeous smoking jacket. A deliberate and repeated comparison was made between the ‘rugged’ body of the working man and the effeminate clothes and body of the absent Marquis whose garments were being ‘fought over’ by the women in the crowd.[28]

Decadence denied

When the Daily Mail managed to obtain a rare interview with the Marquis in Dinard after the crash, the first thing the Marquis did was to apologise,

for not appearing before you in peacock-blue plush, wearing a diamond and sapphire tiara, a turquoise dog collar, ropes of pearls and slippers studded with Burma rubies; but I prefer [he said] and have always preferred, Scotch tweed.

The reporter claimed to be ‘astonished. Lord Anglesey was so extraordinarily as other men are. … He is looking very delicate, it is true, but he wears pince-nez, and brown boots, and his hair looks as if it has never known curl-papers’.[29] Whether this too was a conscious performance by the Marquis, it is impossible to know. Decadent or …?

The Other Danger: an introduction

The Other Danger is one of four plays which the Marquis wrote and starred in between November 1902 and June 1903, and the only one that was published.[30] All four plays were adaptations of recent popular fiction or drama, although I do not know the source for The Other Danger. In 1902 two plays, The Voice of the Night (or The Voice in the Night) and Daily Life, were performed on alternate nights with a farce, Magic Beans, in the Gaiety Theatre in Anglesey Castle. A Beater of Women and The Other Danger were in a programme in 1903 with John Madison Morton’s perennial favourite, the farce, Box and Cox. These evenings were all finished off with ‘one of his Lordship’s many dances’.[31] It is difficult to categorise these short plays, and apart from The Other Danger, we are reliant on newspaper accounts and the few photographs that exist, to reconstruct them. There is something of the heightened style of melodrama, but, more importantly, of contemporary French Grand-Guignol.[32] The settings are all contemporary and domestic. There is violence, or the threat of violence, in all of them, and some decidedly Freudian themes of patricide and matricide.[33] Two are concerned with forms of domestic abuse. One of the most striking things about three of the plays is the engagement with a class other than his own, and the poverty brought about by lack or loss of work.[34]

The first drama, The Voice of the Night, was ‘an adaptation…of the well-known French piece, “At the Telephone”’.[35] The part the Marquis played was Pierre Rougon, an escaped convict – a name that would have been familiar to readers of Emile Zola’s twenty Rougon-Macquart novels written between 1871-93. The North Wales Express describes the play as,

a very thrilling piece … A great deal of excitement is caused in the scene where the husband by means of a telephone which connects his office with his home overheard an escaped convict taunting his wife while he is powerless to protect her.

The husband then hears ‘through the telephone his wife’s frenzied appeals for help and Rougon’s savage threats and final murderous shots’.[36] The Marquis’s second play, Daily Life, was based on the opening chapters of the recently published sensational novel, The Turnpike House (1902) by Fergus Hume,[37] which tells ‘the story of a wife whose love is turned to fierce hatred by the drunkenness and cruelty of her husband, a hatred shared as intensely by her ten-year-old son. At a crisis in the gloomy story, the drunken father enters the bare room in which his well-nurtured wife has been reduced by his habits. His son, who had been discussing his father with his mother, greets him savagely knife in hand’. In the novel, it is the boy who ultimately kills the father, but in the Marquis’s version, ‘a savage struggle ensues [in which] the mother plunges the knife her husband has wrested from his son into her husband’s heart, and amid the breathless silence of the audience [the father] falls a corpse on the stage.’ [38] In The Other Danger, patricide becomes matricide when the desperate and out-of-work protagonist unknowingly kills his own mother. A Beater of Women is less overtly violent. This was a dramatization of Israel Zangwill’s novella, ‘The Woman Beater’ (1900),[39] in which a ‘celebrity’ poet and Oxford scholar finds himself provoked to violence by the prevarication and emotional betrayal of his lover.

Performances of The Voice of the Night and Daily Life seem to have found enthusiastic audiences with the Gaiety Theatre, ‘crowded beyond the doors far down the corridor, night after night’.[40] The only comments to have emerged on A Beater of Women are less effusive – that the scenery and the drama were ‘excellent and much appreciated’,[41] and the confectionary in Scene 3 was ‘supplied by a Bangor confectioner’.[42] A similarly muted response is found in reviews of The Other Danger. A performance at Penrhyn Hall (a rather utilitarian venue compared to the aesthetically-brilliant Gaiety Theatre) had only ‘a cordial reception’ from its ‘large and fashionable audience’.[43]

The Marquis’s own performances were, however, generally well-received. At the opening night, as Pierre Rougon, ‘his lordship infused more life into the piece than the rest of the actors, who possessed but an elementary knowledge of their lines, and the voice of the prompter was heard too often…’. Things had improved at a later performance, and

Rougon’s savage threats and final murderous shots, was [judged] a piece of consummate acting, and combined with the furious energy of the scene at the other end of the telephone, enacted by the Marquis of Anglesey and Miss Yates, to hold the audience in a horrified silence…. The tumultuous outburst of applause which lasted several minutes, rewarded the players…[44]

In Daily Life, he also showed ‘very considerable histrionic ability, which, in spite of inevitable traces of the amateur’, really touched and held the audience.[45]

Decadence denied?

What, then, was the relationship of the Marquis’s performances in these plays, when he played ‘a murderous convict sans jewels, sans elegant waistcoats, sans almost everything except a prominent broad arrow’,[46] to the exoticism of his pantomime performances and ornate public self? Can they be deemed in any way ‘decadent’? The decadent aristocrat did not, of course, disappear into the criminal or drunken worker for the audience. Just as his spectators were capable of ‘complex seeing’ in relation to his gender-inversion roles, so too, it can be argued, they saw – and enjoyed – ‘Their Marquis’ within these class-inversion roles. The lack of jewels and elegant waistcoats, the heightened nature of performance demanded by these Grand-Guignol style characters, and the distance between the role and the man they knew, would only have served to remind the audience of the performer’s ‘real’, aristocratic decadent-dandy, self beneath the rags. And while the narrative denies decadence, as we understand it, the action indulges the senses – is as sensation-full – as his patchouli-ed, bejewelled and dancing Prince Pekoe. Rather than sensual pleasure, the violence of the interactions ‘embraces [the] sensations’[47] of fear and horror, of excitement, ‘holding the audience in breathless silence’.[48] To bastardise David Weir’s description of decadence, the Marquis of Anglesey’s performance in at least three of these plays, seems to have elicited a response, ‘a delight in disgust’, an enjoyment of ‘things to which people who have normal taste react to with revulsion’[49] – criminality, drunkenness, violence leading to mariticide, patricide and matricide. As with all performance, the pleasure elicited is only temporarily ‘allowed’ before normal tastes are restored and tumultuous applause is given.

The connection between Decadence and these performances may only be part of the historic cultural moment, but the connection is there in the person and performance of the 5th Marquis of Anglesey.

THE OTHER DANGER

A Drama in One Act

Written and adapted by

THE MARQUIS OF ANGLESEY

Published by Jarvis & Foster, Bangor n.d.

CASTE [sic]

Mrs Hayes. … … … … Mrs. Freshwater

Mrs. Durant … … … … Miss E. Rowland

Mrs. Taylor … … … … Miss B. Trevelyan

AND

Alice (Havery’s wife) … Miss M. Yates

Smithson (a Police Officer) … … Mr. E. O. Freshwater

Dr Nugent (A Doctor)

and … … … Mr. G. Alexander

Jim (a workman)

AND

George Havery … … THE MARQUIS OF ANGLESEY

Scene: Mrs Hayes’ Garrett at Brixton

THE OTHER DANGER

OUTSIDE – Voices heard shouting and calling

Mrs Taylor. Mrs. Hayes, are you there? It’s me your landlady!

Jim. We’ll have to break down the door!

Omnes. Mrs. Hayes! [There is a cracking and they break down the

door, and rush in and get near the bed.]

_____________

Mrs. Durant. I believe she is dead!

Jim. We’ll see! Mrs. Hayes? [he shakes her.]

Alice. No! I see her lips moving. Mrs Hayes! Mrs. Hayes!

Mrs. Durant. Let’s see? Yes, I think I saw her moving slightly!

Alice. [who has taken the broken looking-glass from the wall.] Put this mirror to her lips and we shall soon see.

Jim. Give it to us then.

Alice. Yes, she is alive.

Jim. Really?

Alice. Look at this dulness [sic] on the mirror; that is her breath.

Jim and Mrs Durant Quite true.

Mrs Taylor. Where?

Alice. Look here.

Mrs. Taylor I see nothing.

Alice. I tell you she is not dead.

Mrs. Durant. Look she’s moving the sheet.

Jim. See, she’s looking at us. [To Mrs. Hayes.] Yes, it is us, Mrs Hayes; your friends.

Alice. What’s the matter with you?

Mrs. Durant. As we did not see you come down stairs lately, we came up to see …

Mrs. Taylor. Well!

Alice. She is not dead.

Jim. Oh! All but.

Mrs. Durant. As she sees us, surely she can hear us.

Mrs. Taylor. Well, what is it, Mrs. Hayes? You are not well. We have come to see you… No, it is not for the rent…. Where are you suffering? Point out to us where you feel ill. You can hear me? She can’t hear…. What shall we do? …Perhaps she is really ill!

Alice. Perhaps it’s from hunger?

Jim. Here’s a plate of stew ----

Mrs. Durant. What shall we do?

Mrs. Taylor. Shall we let the police know?

Alice. Better get a doctor.

Jim. Or both ---- Shall I go?

Omnes. Oh yes! Let’s go. [Exit.]

Mrs. Durant. Her head is rather low; shall we lift her head up a bit?

Alice. There you are!

Mrs Taylor. How she stares at me! Where do you suffer, Mrs. Hayes? Where? [To Alice.] You ask her. I think she owes me a grudge for having made her come a week ago to wipe her feet on the mat. You understand, as I have to clean the stairs, I think I have a right to pass a few remarks to my lodgers.

Alice. I think you are mistaken.

Mrs. Durant. Come!

Mrs. Taylor. If I ask you to wipe your feet, it’s because it’s the rule of the house. There’s a printed notice …. For which I paid a shilling …. Well, the least thing one can do, when one comes in, is to wipe one’s feet … [To Alice.] I can’t stop any longer. I must go down stairs. [To Mrs. Hayes.] I shall tell the doctor you are waiting for him, …. And that he must look after you well. [Exit.]

Mrs. Durant. What misery!

Alice. Yes. Like everywhere where there is poverty.

Mrs. Durant. I say, it appears she has not always been like that. Old Mrs. Hayes, if one can believe what the gossips say, used to live a rather gay, easy, and happy life.

Alice. As for what they say!

Mrs. Durant. From what I’ve heard, she had someone who kept her very well; but, you know, she never spoke to me no more than she did to you …. nor anybody else …. And you know nobody was ever allowed in here …

Alice. That she had this or did that .… what matters? The principal thing now is that she is at death’s door.

Mrs. Durant. Perhaps that’s all the better for her.

Alice. Good-bye to poverty; good-bye to days of hunger; this will end her misery. For what life reserves us ….

Mrs. Durant. Are you still unhappy at home?

Alice. More than ever.

Mrs. Durant. Hasn’t your husband found any more work yet?

Alice. Alas! no. It is not easy to find a solution. Before, George used to find odd jobs here and there, starting early in the morning, returning late at night, gaining only a few pence a day, but still it was always that. But now that is all over, and there is nothing but misery, misery, misery. Ah! one must have courage to stand that long and remain honest. Oh! if we had got no children, all would soon be over. It is for them we suffer and we live, and we give up our one and only bit of bread .…

Mrs. Durant. Come …. Come. [A knock heard at door.] Someone knocked. [She goes to open door.] I expect it’s the doctor.

Havery. Mrs. Durant, is my wife there?

Mrs. Durant. Come in, Mr. Havery; yes your wife is here.

Alice. Its [sic.] you …. Well, what luck! Have you found something to do?

Havery. No.

Alice. Still no work.

Havery. Yes. They told me to return …. They promised me ….

Alice. Ah! promises …. Even heaven abandons us!

Havery. It is just my luck to be abandoned. …. As a child my mother abandoned me …. It was bound to continue. [Pointing to Mrs. Hayes.] And her, what’s the matter with her?

Alice. We don’t know.

Mrs. Durant. Probably a fit.

Havery. At her age?

Mrs. Durant. Yes. …. I think its [sic.] the end. [Knocking heard.] I say you’ll excuse me a moment.

Alice. Are you going?

Mrs. Durant. Someone is knocking; its [sic.] my husband who is calling me from below …. I’ll come back. [Exit.]

Havery. I say, Alice.

Alice. Yes, what is it?

Havery. Her eyes are open.

Alice. Yes, I know, but I don’t know what to do.

Havery. Have they gone for the doctor.

Alice. Yes, Jim went.

Mrs. Durant. I say, I have just met a man who was asking for you. You know the person who came this morning.

Alice. [Quickly.] Oh! yes I know, I know, it is the bailiff. …. I told him you would not be in all day. …. Stay, I’ll go.

Havery. The bailiff, pah! For what remains to be taken. Poor Alice …. Poor kids! …. Halloa! Why, she’s moving, what’s the matter with her? …. Come.…. What is it? …. You want to get up? No, no, you can’t. …. The doctor will be here in a minute. …. To lift you up. …. Straight. …. Yes, there, there, calm yourself.

Mrs. Hayes. Mo…. Mo ….

Havery What!

Mrs. Hayes. Mo…. Mo …. Ney.

Havery Oh! money. She is delirious.

Mrs. Hayes. There. [Pointing to the floor.]

Havery There!

Mrs. Hayes. Mo…. Mo …. Ney … Ney.

Havery Yes, yes, money. I understand. [Aside.] Poor woman.

Mrs. Hayes. Money.

Havery [Laying her down.] Gently, gently.

Mrs. Hayes. Money … my….my …. mon … there.

Havery. This persistence; I have known before.

Mrs. Hayes. Mine …. there.

Havery. There is money there! but where?

Mrs. Hayes. There.

Havery. There. Hallo, it sounds rather hollow, hallo this opens.

Mrs. Hayes. Yes …. Yes ….mine …. Mine.

Havery. [Who has lifted up a board and found a box.] Bank notes. … Gold. … Silver. …Good gracious, what a fortune! [Goes near candle and examines it all.] Yes, quite a big fortune. The old gossips spoke the truth then. … In days gone by old Mrs. Hayes must have had a good old time, and like so many other people become miserish! Yes quite a fortune. … oh! yes, she had a tidy lot of money. … whilst we poor devils were starving with hunger, old Mrs. Hayes was contemplating her wealth. [Looking at her.] I suppose you thought you silly old fool, that you could take your wealth with you when you died. Only think of all the good you might have done, of all the joy you could have given the poor, and all the worthy charities you could have helped. … and what are you going to do with your money now, pray? Come, tell me what do you intend to do with it? To whom do you want it to be given? What must we do with all this money?

Alice [Enters.] Oh! my George!! my George!!

Havery What’s the matter?

Alice The bailiff wouldn’t listen to anything. …. Oh! what is to become of us?

Havery I say, did not Mrs. Hayes say anything just now to you?

Alice. No.

Havery What, not a word!

Alice Not a word. … Why do you ask?

Havery Oh! nothing. … only an idea. … Halloa, she’s quiet again.

Alice. I don’t think she will get over it. The doctor will come too late. Look at the awful way she is looking at us. [To Mrs. Hayes.] Do you recognise us Mrs. Hayes?

Havery [Impatiently.] Oh! leave her alone. I say what are the kids doing?

Alice. They are down stairs.

Havery Go and put them to bed, it will be less cold for them. … you can come up afterwards! Have they eaten?

Alice Hardly anything.

Havery Go, go!

Alice Well! And you, arent [sic.] you coming?

Havery We can’t leave her alone.

Alice How queer you look. … aren’t you well?

Havery Yes! I’m alright!. … go. [Exit Alice. Havery goes to the door and sees that all is quiet and no one about.]

Mrs. Hayes. [Who sits up in bed again.] Thi …. Thieves!!

Havery [Rushes at her.] Thief! They’ll come …. I shall be caught …. Hold your tongue …. Damn it woman, hold your tongue. [He throws her back on the bed and puts his hand over her mouth. Then catches her by the throat.]

Mrs. Hayes. Mur! …. Murder!!

Havery Hold your tongue! good God hold your tongue! Damn it she bites. [Mrs Hayes struggles and cries out, Havery terrified, squeezes her throat and finally strangles her.] Now I have gone and done it, I’ve killed her. Oh! well after all she shouldn’t have made such a noise. [Goes and gets money out. White lime to shine on Mrs. Hayes’s face.] Ah! My God what a temptation! Remain honest and die of starvation, or the other danger, steal, and all my little ones and wife will have bread to eat. … Ah! Well what matters it if I go to prison, so long as they are provided for and happy. We are sorely in need of a little happiness and joy. Well! I’ve got her money. Now I shall be able to eat every day, and my kids will be able to be fed also. And I was about to hesitate, fool that I was. I wonder what she used to do with her money? [Looking at his hand.] Her old teeth have bitten my finger to the bone. [Slight noise.] WHAT’S THAT? I thought I saw her move; pah! What nonsense! [Goes and looks at her bed.] No! … no! no! she’s dead right enough. [He puts pocket book in his pocket.]

[Enter Mrs. Durant, Mrs. Taylor and Alice.]

Mrs. Durant. [Goes up to bed.] Well!

Havery Well!

Mrs. Durant. Well its all over, she’s dead!

Alice. Yes all over.

Mrs. Durant. Oh! Holy Mary. You said it would not be long, And the doctor, oh! for poor people they never hurry. [Enter Mrs. Taylor.]

Mrs. Taylor. Well! Are you better?

Omnes. SHU!

Alice. Dead!

Mrs. Taylor. Dead! And she hasn’t even paid her rent! The landlord will be down on me now! Well did she speak before dying?

Havery No. [Mrs Durant has cleared the table by the bed and put a candle on it and lights it.]

Mrs. Taylor. Ah!

Mrs. Durant. We don’t know her family!

Mrs. Taylor. Beggars have no relations!

Alice. Where does she come from?

Mrs. Taylor. I don’t know …. Now you see what it is to be like a tomb and never talk, and never to tell anyone who you are or where you come from, and so you die like a dog without a single friend near you.

Mrs. Durant. Someone will have to lay her out and watch her tonight.

Mrs. Taylor. I can’t; I’ve got my lodgers and flats to look after.

Mrs. Durant. I would have done so willingly, but my husband is alone down stairs, and I can’t leave him.

Mrs. Taylor. Well, what’s to be done?

Alice. We might watch her!

Havery. We!

Alice. But of course it’s the least we can do poor woman!

Havery. Alright.

Mrs. Durant. That’s alright. … and I’ll bring you up some nice hot coffee.

Mrs. Taylor. [To Mrs. Durant.] They are bad payers, but still they are kind hearted people.

Mrs. Durant. Why, of course they are.

Mrs. Taylor. Well, I’m off.

Mrs. Durant. I’m following you. So long! [Exit.]

Havery. I say, why do we stop? We shall only catch our death of cold here, without a fire. We had much better go down stairs.

Alice. It’s just as cold downstairs as it is here, and then the poor old woman, we can’t leave her all alone; and besides, we promised to stay.

Havery. Shall I go and get a bite for you to eat?

Alice No. Don’t go and leave me; I should be afraid to be here all alone with a dead person.

Havery Why, you need have no fear of a dead person.

Alice It doesn’t matter! I should be frightened all the same. Please don’t go and leave me!

Mrs. Taylor. [Outside, opening the door.] This way, sir, please. [Havery trembles. Alice gets up and arranges things.] Come in, sir … there she is, sir.

Smithson [To Doctor.] See Doctor. [To Mrs. Taylor.] How long is it since she had not been downstairs?

Mrs. Taylor. Three days exactly. It was just after the postman called.

Smithson. [To Dr. Nugent.] Doctor, will you kindly go and see her, and state the cause of death. [He goes to bed and lowers sheet.]

Mrs. Taylor. We aren’t going to leave her like a dog; I can’t stay and watch her, because I have my flat to look after…. But Mr. and Mrs. Havery will, as they were here when she died.

Smithson. Oh!

Mrs. Taylor. She hadn’t paid her rent….

Smithson. We’ll see about that later. [To Doctor.] Have you done Doctor? Will you give me the certificate of death?

Dr. Nugent. [Who is examining Mrs. Hayes.] One moment, if you please.

Smithson. [To Mrs. Durant.] Alright. Did you know anything about her family?

Mrs. Durant. No. She used to call herself Mrs. Hayes. … But perhaps, if we searched her things we may find some papers relating to her.

[The Bailiff looks about, then goes to chest of drawers, opens them, and finally finds a paper.]

Smithson. Yes! This seems like a will.

Omnes. Oh! A will. Well at last we shall know something.

Dr. Nugent. Mr. Smithson, it will be impossible for me to give you permission to have this woman buried!

Smithson Why?

Dr. Nugent. Because this woman has not died a natural death, … she has been murdered!

Omnes and Smithson. Murdered!

Mrs. Taylor. Why that’s absurd. We were all here when she died.

Dr. Nugent. I maintain what I say, … look here Mr. Smithson, these swollen lips show something hard was pressed on her mouth. … Then there is blood on her face, her neck shows signs of strangulation; look at those finger marks!

Smithson. You are right. [To Mrs. Taylor.] Was she still alive when you broke in the door?

Mrs. Taylor. Yes; we can swear to that.

Smithson [To Mrs. Taylor.] Come now, you just told me that you were by her when she died?

Mrs. Taylor. Ah! No; not me. [Pointing at Alice.] Mrs Havery.

Smithson. You were?

Alice. Yes; that is to say!

Smithson. That is to say?

Alice. My husband remained alone with her for a few minutes…

Smithson [Looking at Havery.] You saw her die?

Havery. Yes.

Smithson. And you were alone with her?

Havery. Yes, sir.

Smithson. And she died quite naturally?

Havery. Of course.

Dr. Nugent. I swear this woman has been murdered.

Smithson. And you still stick to it, that you saw her die quite naturally.

Havery. Yes, I do.

Smithson. I’m afraid I shall have to retain you for a time in custody.

Alice. But why?

Havery. But surely, sir, you don’t suspect for a minute that I ….

Mrs. Taylor Oh! Mr. Smithson. I’ll answer for him like I’d answer for myself.

Smithson. Come, come. What’s your name?

Havery. Havery.

Smithson. Where were you born?

Havery. At Bolton.

Smithson. In what year?

Havery. The 26th January, 1866.

Smithson. Who were your parents?

Havery I never knew them.

Smithson. What did you say your name is?

Havery. George Havery.

Smithson. George Havery. Well, in this will the deceased woman leaves all her fortune to her natural son, George Havery, born at Bolton, on 26th January, 1866.

Havery. Eh! What! What did you say? That this woman was my mother! Oh, no, no, no, no, its impossible.

Alice and Smithson. Why?

Havery. I tell you its impossible. … What! Have I murdered my mother?

Smithson. What do you say?

Alice. He is mad! Don’t listen to him, George! Come George!

Havery. Oh! leave me alone.

Smithson. You confess then?

Havery. Yes, yes, I confess!

Alice. George! For pity’s sake [she falls at his feet].

Havery. Leave me alone! Leave me alone. [to Smithson]. I tell you I murdered her … Yes, I murdered her to rob her …. To take this [showing pocket book with money]. You don’t believe me? I tell you I was ALONE with her, and was stealing her gold when she began to call out and then … then I strangled her! Ah! My God those eyes, those eyes which stare at me. … take me away, …. damn it, take me away, I won’t have her stare at me. …. Do you hear, I won’t! I won’t! Ah for God’s sake, take me away! Take me away! My God, take me away! [Falls into a swoon.]

Notes

[1] Weekly News and Visitors’ Chronicle for Colwyn Bay etc., 5 August 1904, p. 2. The original song, ‘Lardy Dah! Lardy Dah!’, was composed in 1880 by E.V. Page and sung by cross-dress performer, Nelly Power.

[2] Penny Illustrated Paper, 31 December 1904, p. 14.

[3] Courtesy of my psychoanalyst friend with whom I have many fruitful ‘discussions’ about the 5th Marquis, but, sadly, I have neither the competence nor confidence to pursue this angle now.

[4] Minna, Dowager Marchioness of Anglesey (1843-1931). Lived at the Villa L’Ermitage in Versailles from the late 1890s till her death. She was an inveterate collector, and in 1900 purchased the entire Art Nouveau room exhibited by the department store, Le Bon Marché, at the Paris Exposition and installed it in her villa.

[5] ‘Diana-up-to-date’ in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 4 January 1902, pp. 24-6. The writer suggests that the audience might all die of ‘patchoulic asphyxiation’, so strong was the smell. The car exhaust story originated in the American papers then spread in the UK. See: Arthur Symonds ‘Being a Word on Behalf of Patchouli’ in Jane Desmarais and Chris Baldick, eds Decadence: An annotated anthology (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012), pp. 34-37.

[6] Quoted in Christopher Simon Sykes, Black Sheep (London: Chatto & Windus, 1982), p. 215.

[7] Bognor Regis Observer, 22 March 1905, p. 7. The Paget family had sold their London house, Uxbridge House, in the 1850s.

[8] Daily Express, 11 August 1902, p. 9; Daily Express, 31 July 1902, p. 1.

[9] The Burton Evening Gazette described him as ‘flushed with pleasure at the encores of small shopkeepers and his own flunkies’. March 24, 1905. This disparagement by the Burton papers owes much to that town’s problematic relationship with the Marquis, who gained two thirds of his income from industries in and around the town, but only visited it twice. However, the language is telling. The contumely heaped on the Marquis is that of the twentieth century industrialised community for the effete and decadent aristocrat and a sycophantic audience drawn not from his own class, but the trading and servant classes. His Welsh mansion, Plas Newydd, stands, like Des Essientes’s villa at Fontenay, ‘in a lonely spot … far from all neighbours’, and ‘too far out for the tidal wave of Paris [or London] life to reach him’ (although the marquis’s mansion in no other way resembles Des Essientes’s retreat; Fontenay was just 5 miles from the centre of Paris, whereas Plas Newydd is 280 miles from London). Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1959), p. 24.

[10] ‘Sigma’ in Burnley Express and Advertiser, 16 August 1902, p. 7.

[11] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 6 March 1903, p. 6.

[12] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 16 January 1903, p. 5.

[13] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 6 March 1903, p. 6.

[14] Ethel Hyde/Evelyn Hope diary, Thursday 5 June 1902. Private collection.

[15] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 17 January 1902, p. 3.

[16] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 16 January 1903, p. 5.

[17] Lichfield Mercury, 2 September 1904, p. 6.

[18] Washington Post, 11 September 1904, p. 6.

[19] Yorkshire Evening Post, 14 January 1902, p. 2.

[20] Reminiscent of Théophile Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin.

[21] Revealed in the court case when the Marquis was sued for the ‘theft’ of his theatre company in 1903.

[22] George Moore Confessions of a Young Man (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1952), p. 51.

[23] Equivalent to £42,741,808.00 in 2017. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/, accessed 17 January 2022. Details of the debts and subsequent insolvency proceedings were reported in almost all the national newspapers between March and August 1904.

[24] V. de Frece, Recollections of Vesta Tilley (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1934), p. 125. The waistcoats can be seen at the Vesta Tilley collection in Worcester. https://www.worcestershire.gov.uk/info/20230/archive_and_archaeology_projects/1127/the_vesta_tilley_collection, accessed 10/03/2022.

[25] There isn’t space here to explore the relationship between decadence and dandyism. See David Weir, Decadence: a very short introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 5-6.

[26] North Wales Chronicle, 27 August 1904, p. 5.

[27] Burton Chronicle, 1 September 1904, p. 5.

[28] Lichfield Mercury, 26 August 1904, p. 8; 2 September 1904, p. 6.

[29] Daily Mail, 18 October 1904, p. 5.

[30] The publishers were Jarvis and Foster, local Bangor printers, who also produced his posters and programmes. I am excluding the adaptation, A Runaway Boy (1899-1903), as this appears to have been a straight lift from the original musical comedy.

[31] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 3 April 1902, p. 5.

[32] For the history of Grand-Guignol and its relationship to social realism, see Richard J. Hand and Michael Wilson, Grand-Guignol: The French Theatre of Horror (Exeter: Exeter University Press, 2003), pp. 3-25. It may be just a coincidence that both the Théâtre du Grand-Guignol and the Marquis’s Gaiety Theatre were old chapels and retained their past in their present incarnation.

[33] On first reading The Other Danger, I was reminded of the ending of Emile Zola’s highly dramatic, psychological, dramatization of his novel, Thérèse Racquin (1873).

[34] These performances took place against the backdrop of the notoriously brutal lockout of the striking Penrhyn slate miners (1900-03) by Lord Penrhyn, whose castle was just over the Menai Strait from Anglesey Castle. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/penrhyn-castle/features/penrhyn-castle-and-the-great-penrhyn-quarry-strike-1900-03, accessed 27 March 2022.

[35] Liverpool Echo, 1 December 1902, p. 3. Au Téléphone (1901) by André de Latour, comte de Lorde (1869–1942), ‘Le Prince de la Terreur’. This two-act Grand Guignol play was made into a 4-minute film in 1906 as Terrible Angoisse (Terrible Anguish).

[36] Unidentified cutting, Mavis Hope’s cuttings album, Plas Newydd.

[37] Fergus Hulme, The Turnpike House, serialised in the Cheshire Observer 18 January 1902 – 26 April 1902. (http://newspapers.library.wales/view/4281236/4281238), accessed 10 October 2019. Then published by John Long, London, in 1902.

[38] Liverpool Echo, 1 December 1902, p. 3.

[39] Israel Zangwill (1867-1936). Originally published in The Universal Magazine in 1900, and Grey Wig or stories and novelettes (London, William Heinemann, 1903). The Marquis and Zangwill make odd bedfellows; the peer a member of the conservative, Primrose League, and Zangwill a cultural Zionist and supporter of such radical causes as women’s suffrage.

[40] Liverpool Echo, 1 December 1902, p. 3.

[41] The Chester Courant and Advertiser for North Wales, 20 May 1903, p. 8.

[42] London Daily News, 16 May 1903, p. 5.

[43] Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 3 April 1902, p. 5; North Wales Express, 3 April 1902, p. 5.

[44] Unidentified cuttings, Mavis Hope’s cuttings album, Plas Newydd.

[45] Liverpool Echo, 1 December 1902, p. 3.

[46] Evening Express, 26 November 1902, p. 8.

[47] Unidentified cutting, Mavis Hope’s cuttings album, Plas Newydd.

[48] Liverpool Echo, 1 December 1902, p. 3.

[49] Jane Desmarais and Alice Condé, eds. Decadence and the Senses (Cambridge: Legenda, 2017), p. 3.