Dancing decadence: The Norfolk rave scene

Dr Adam Alston (Goldsmiths, University of London)

With photos by Holly Mabee and Molly Macindoe, and curatorial support from Louise Render

Fig. 1: Rushford Quarry, Norfolk, 2003. Brains Kan. Photo by Holly Mabee, courtesy of Louise Render.

It’s five minutes to midnight in the early 2000s, and I’m parked in a car full of teenagers in a petrol station near Thetford, just off the A11. This is Boudica country: a forested netherworld that provides an escape route out of rural Norfolk and into the flatlands of the fens. We’re waiting on the location of a rave. At the time you had to call a number at a designated time to be told where to head, or sign up for text messages once that became a thing. It’s a lot harder to shut down a rave when everybody arrives at once – at least not without causing a riot. You’d be given a general vicinity, and then you waited… And so we waited, immersed in the yellow gloom of the forecourt in a beaten-up VW Golf with fewer seats than people, one with his eyes shielded by sunglasses despite the time and place, another pulling back scraggly hair to gulp on a bottle of Lucozade.

Midnight. The party line is up and running, the car revs into life, and we make our way to a muddy track nearby. Muted breakbeat erupts somewhere in the distance, through fir trees and across ploughed fields – a sonic compass guiding the rest of the journey on foot.

Fig. 2: Just off the A11 in Thetford, Norfolk, 2005. Equality Cohesion. Photo by Holly Mabee, courtesy of Louise Render.

Some of the raves in rural Norfolk in the late-1990s and 2000s were led by established free party crews like Brains Kan, Equality Cohesion, and Planet Yes, but most were nameless, DiY affairs in woods, fields, clearings, quarries, and paddocks. They were sensual stimulants that cast us into a deeper, more profound sense of immediacy and connectedness with one another as much as our environment in places that were relatively cut off from public service infrastructures – in the more remote areas, that is, where I lived with most of my friends. These nights were often accompanied by a debilitating entropy the next day, ear drums attuned to a tinnitus ring and trainers still caked in mud, but this was not much of a concern when savouring synaesthetic rhythms and melodies that seep into the flesh, the shimmering sweat that cools the skin in the night time air, the dampened shirt of a new-found friend and the feeling of their embrace, burning up and burning out in the rising sunlight of a day that arrives too soon.

Fig. 3: Rushford Quarry, Norfolk, 2003. Brains Kan. Photo by Holly Mabee, courtesy of Louise Render.

These raves were not just about chasing euphoria, as pleasurable as that could be; they were also intensely social, in spite and because of the relatively isolated locations in which they took place. The pleasures they aroused were ultimately contingent on their being experienced with and in relation to others, both known and unknown.

There are several reasons why I wanted to write about the Norfolk rave scene in the context of this blog, which is concerned first and foremost with ‘decadence’ and ‘performance’. Firstly, this post is adapted from a provocation I gave at a recent conference on ‘Neo-Victorian Decadence’.[1] I wanted to play with how far the ‘neo’ in its title could be stretched, which participates in a wider strategic ambition that has to do with acknowledging while also disrupting the ways in which decadence is tied to the late-nineteenth century as a critical concept, and as a style of (self-)presentation, writing and making. The familiar faces of nineteenth-century literary decadence do not come readily to mind when thinking about rural raves, which are a world apart from the hyper-refinement or perversion of decorum of the kind you might find in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s À rebours (1884), for instance, or Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Nonetheless, raves share in a sense of decadence that understands it as the cultivation of a taste for pleasures that many might find distasteful, self-destructive or socially corrosive (however arbitrary such judgements may be). Also, meticulous cultural refinement is at stake, although it has to do with the evolution of niche musical subgenres and practices. And dance music cultures have been pathologised and criminalised as a social and moral scourge in ways that reflect the standard tropes and fears that circulate in conservative diagnoses of the decadent society: a reactionary view of society based on a belief that moral and behavioural standards are falling foul of a debilitating rot. Finally, despite being branded as pariahs in politics and the press, those participating in raves often reclaimed disparaged ‘counter’ culture as a basis for developing individual and collective identities, which taps into a long history of socio-cultural tactics and strategies that stretch back through the nineteenth century and especially the decadents who were caught up in their own culture wars at the time. There are several reasons, then, why it might be useful to think about the ‘decadence’ of rural rave culture in these specific senses - although in the spirit of a blog post and indeed the raves themselves I’m sharing these ideas at a point when I’m still wading through their connections and resonances.

The second reason why I wanted to write about the Norfolk rave scene in the context of this blog is to try and get at a sense of decadence that understands it not as a disembodied concept about bodies, which has served studies of late-Victorian and post-Victorian literature very well, but as an embodied practice that arouses and acts as a vector for the transmission of countercultural desires and pleasures, which might serve Performance Studies better.[2] A third, complimentary reason is that this post provides a welcome opportunity to widen the range of practices that might fall under the umbrella of the Staging Decadence project, which is largely concerned with theatre, although not exclusively. In this case, it means addressing performance in the expanded field – quite literally, as it turns out, given that I’m mainly concerned with dancing in fields.

Fig. 4: East Runton, Norfolk, 2003. Crossbones / K.D.U / Nine Bar / TechnoNotice / Tribe of Munt / Molotov. Photo by Molly Macindoe.

Finally, focusing on the Norfolk rave scene enables us to envisage a very different understanding of the contemporary relevance and desirability of decadence by complicating a misleading caricature that understands it to be both apolitical and antisocial.[3] I only attended Norfolk raves sporadically between 2002 and 2008, or thereabouts, and was only ever on the fringes of that scene – I am a fan of but not an expert in dance music, and this post builds on a specific but limited window of experience – but in that time it became clear that many of those who attended and who were involved in organising them did so because they cared about creating social environments for free expression that were not like anything available to them in licensed venues (with the possible exception of ticketed dance music festivals, which are less likely to appeal to someone drawn to the anarchism of free parties). The cultural and musical lineages underpinning these raves were also fundamentally political, both in terms of the politics held by many of those involved (which was very varied, but predominantly left and left-liberal), and because of a clear disaffiliation from or an adversarial relationship to law enforcement and ‘the count of the uncounted’ in electoral democracies, to borrow a memorable phrase of Jacques Rancière’s.[4]

Fig. 5: Cholsey Downs, The Ridgeway, Oxfordshire, 2000. Chaos / Crossbones / Mainline / Urban Warfare. Photo by Molly Macindoe.

Norfolk raves around Y2k were informed by two main cultural and musical lineages. The first can be traced back to the anarcho-punk and traveller free party scene in British cities and rural fringes in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as rural fairs in the East of England. I’ll be returning to these shortly. The second relates to the music that was played at these raves, which is indebted to the evolution of DJ-led dance parties in New York in the 1970s and club music in New York and Chicago in the 1980s, as well as the trans-Atlantic influence of these scenes on British parties and clubs in London and the north of England in the late-1980s. Another influence was the Ibizan tourist and club scene, which fed into the popularity of acid house music in the UK in the late-1980s,[5] although the ‘Second Summer of Love’ in 1988 and the pioneering work of sound system collectives like Spiral Tribe (est. 1990) and Exodus (est. 1992) in the years that followed helped with establishing ‘rave’ as a distinctive scene outside of metropolitan clubs and warehouses, traversing and innovating a wide range of genres and styles including techno, breakbeat techno, house, and – later – the hardcore scene that precipitated the rise of jungle and drum & base.

Vid. 1: For a striking introduction to the evolution of electronic dance music in the UK from disco to Northern Soul, house and rave, see Mark Leckey’s hypnotic film Fiorucci made me Hardcore (1999).

I’m not the first to consider the ‘decadence’ of dissident dance cultures. A recent contributor to the Decadence Studies journal Volupté, William Rees, explores a number of intriguing connections between decadence and disco. Rees argues that both decadence and disco were ‘othered’ relative to the cultural mainstream, paying particular attention to queerness, dandyism, and excessive refinement. He also explores how both cultures came to be seen to represent ideas of urban decline, drawing on popular and influential framings of New York in the 1970s as a crime- and poverty-stricken city in films like Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976), although depictions of New York as a city ‘infested’ with degeneration and moral decay are also exaggerated and misleading relative to the day-to-day and night-to-night reality of living in the city.[6]

I do not wish to cover the same ground as Rees in this post, other than to highlight the importance of gay, Latin American and African American constituencies in a mixed dance party scene in New York in the early 1970s (a period that precedes the identification of disco as a coherent genre in 1973). These dance parties – which went on to inform the emergence and evolution of disco and the club cultures surrounding it – broke their initial groves at venues like David Mancuso’s Loft in downtown Manhattan and the Sanctuary in Hell’s Kitchen, which both had entry policies that drew mixed crowds including (and most significantly at the time) gay, Latin American and African American revellers. The roots of this scene can also be traced to East Harlem rent parties in the 1960s, which were centred around Black and gay communities, and as a musical genre disco can be traced back through Philadelphian and Harlem soul and R&B.[7] My own interest in the ‘decadence’ of disco has more to do with these musical and cultural influences than it does with the civic state of New York as a metropolis, especially the ramifications of the particular terminology surrounding the dismissal of disco at the time. Deriding discos and the people who danced at them as ‘decadent’ and ‘unnatural’ by the end of the 1970s (typified in the derogatory slogan ‘Disco Sucks’) was as much a homophobic attack on gay communities as it was a sexist slur and a racist affront to African American and Latin American culture and identity.[8]

Vid. 2: Ron Hardy live at the Muzic Box in 1985. Ron Hardy was an important pioneer of Chicago house, and a key bridge between disco and house. His sets were also instrumental in the development of acid house, and influenced Phuture’s ‘Acid Tracks’ (1987), which is widely considered the first acid house recording.

Disco’s lines of flight in the late-twentieth century are many and varied (see Vid. 1), but most histories of UK rave tend to highlight the emergence of Chicago house in the mid-1980s as an important steppingstone: ‘reminiscent of disco, but stripped of its bare essentials, raw and machine-driven’.[9] Associated with producers and DJs like Ron Hardy (see Vid. 2), Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk and Frankie Knuckles (once a regular attendee at Mancuso’s Loft), Chicago house replaced disco’s more coherent melodic refrains with sampled vocal snippets that contributed to the hypnotic rhythmic texture of the whole. Chicago house as well as New York garage and Detroit techno (via the pioneering German synth outfit Kraftwerk) are the cornerstones of dance music as we know it today, but it is Chicago house that grew most explicitly out of disco’s gay, African American, Latin American, and countercultural roots. The optimistic inflections of early UK acid house also echoes the optimistic spirit of disco, although by the time I was attending Norfolk raves in the early 2000s much of that optimism had given way to more intense hardcore subgenres. Where the optimism of early UK acid house provided a counterpoint to Thatcherism, these were the years of Blair and Brown, of cool Britannia, a time when things could only get better – years, in other words, of delusion. It was only fitting that its soundtrack in those fields had a darker underside, despite the sociality and euphoric feelings of pleasure that the music could stimulate so readily in the right context and circumstances.

Vid. 3: Original Brains Kan mix from 6 July 2002. Brains Kan were revered organisers of Norfolk raves between 1998 and 2007.

Dancing in woods and fields in predominantly rural counties like Norfolk also grew out of an alternative set of influences that seemed to have little to do with its trans-Atlantic roots, at least at first glance. Firstly, most of the ravers I knew were aware of the Black music cultures that anticipated and underpinned the rave scene, because Jamaican breakbeat and dub-reggae formed a part of that scene.[10] However, Norfolk raves also trace their lineage to the East Anglian fairs of the 1970s, with many of the organisers augmenting the countercultural spirit and outlook of their parent’s generation (some raves were also organised by older ravers who grew up in the ‘70s, and the Norfolk rave scene maintains close relationships with rural music festivals both large and small).[11] The fairs were an ‘avowedly rural project’ geared around the sharing of countercultural goings-on in fields: folk and psychedelia, liberatory education, LSD, CND, painted caravans, horse trading, naturists, druidism, medievalism, ‘sublime degeneracy’ stimulated by a passionate critique of modernity... These features gave the fairs a distinctly decadent flavour, particularly their merger of Romantic nostalgia and intoxicating excess, but they also catered for a predominantly white demographic in a predominantly white county.[12] The roots of dance music culture in African American, Latin American and gay music and subculture was not so much displaced in the Norfolk context, then – it was a sonic presence – but that presence was conflated with a more overtly white, rural and heterosexual (if not always heteronormative) countercultural tradition, as well as predominantly white punk / DIY influences. Many of us simply took the music as ‘ours’, without realising whose histories we were borrowing in constructing our own sanctuaries and countercultural havens.

Secondly, as Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson recognise, when ravers in rural areas ‘danced beneath the shifting tinctures of the open sky, what began as American dance musics became entangled within a skein of pastoral imagery’.[13] Where cities undergo cycles of growth, decay and regeneration, offering ravers opportunities to inhabit industrial ruins in the interim, raves in remote rural areas were not reliant on the failures of industrialism so much as the temporary disruption of a more archaic system of land ownership. Alongside concerns around the safety of dancing in unlicensed venues in city centres, the appropriation of land in rural areas and the ways in which it impacted residents in local villages played an important role in the stricter enforcement of laws relating to public nuisance. In 1990, the year of the Poll Tax riots, back bench Conservative Member of Parliament Graham Bright proposed the 1990 Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Act, the so-called Bright Bill, to sanction free parties ‘without the appropriate local authority license’.[14] The Bright Bill was not proposing a new criminal offence, but stricter enforcement and harsher penalties including fines of up to £20,000, six months’ imprisonment, or both.[15] The Association of District Councils, however, proposed to amend the 1974 Control of Pollution Act by making unsanctioned noise a criminal offence.[16] A headline-grabbing week-long free party on Castlemorton Common in Hereford and Worcester in 1992 that was attended by tens of thousands of ravers also amplified calls for legal reform. Finally, the perception of raves as the invasion of an inner-city problem with its inner-city issues raised the hackles of rural landowners,[17] although rural raves were often organised and attended by those living in the countryside – sometimes with the permission of landowners, and sometimes not. The pioneering interventions of Spiral Tribe may have brought urban crowds to remote rural areas, but those living in the countryside were no strangers to countercultural disruption.

Fig. 6: Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2005. Brains Kan / Equality / Real Eyes. Anonymous photographer, courtesy of Louise Render and Lauren Clarke.

Fig. 7: Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2005. Brains Kan / Equality / Real Eyes. Anonymous photographer, courtesy of Louise Render and Lauren Clarke.

All of these factors helped to pave the way for the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act to ease the enforcement of the rave scene’s criminalisation by targeting the playing of amplified music in open-air spaces to groups of one hundred people or more, specifically music that was ‘wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats’.[18] The act also handed the police discretionary power to penalise music and dance gatherings of ten people or more if they were suspected of organising a rave or were deemed a public nuisance. The act also targeted the unsanctioned occupation of private land, as well as activities specific to rural areas – for instance, the sabotaging of hunts. Traveller communities were also disproportionately affected, which led to a dispersal of ‘tekno travellers’ across Europe where they soon faced similar struggles with the law and law enforcement before attempts were made to contain the spread of rave culture by legalising the promotion of festivals in appropriately surveilled venues.[19]

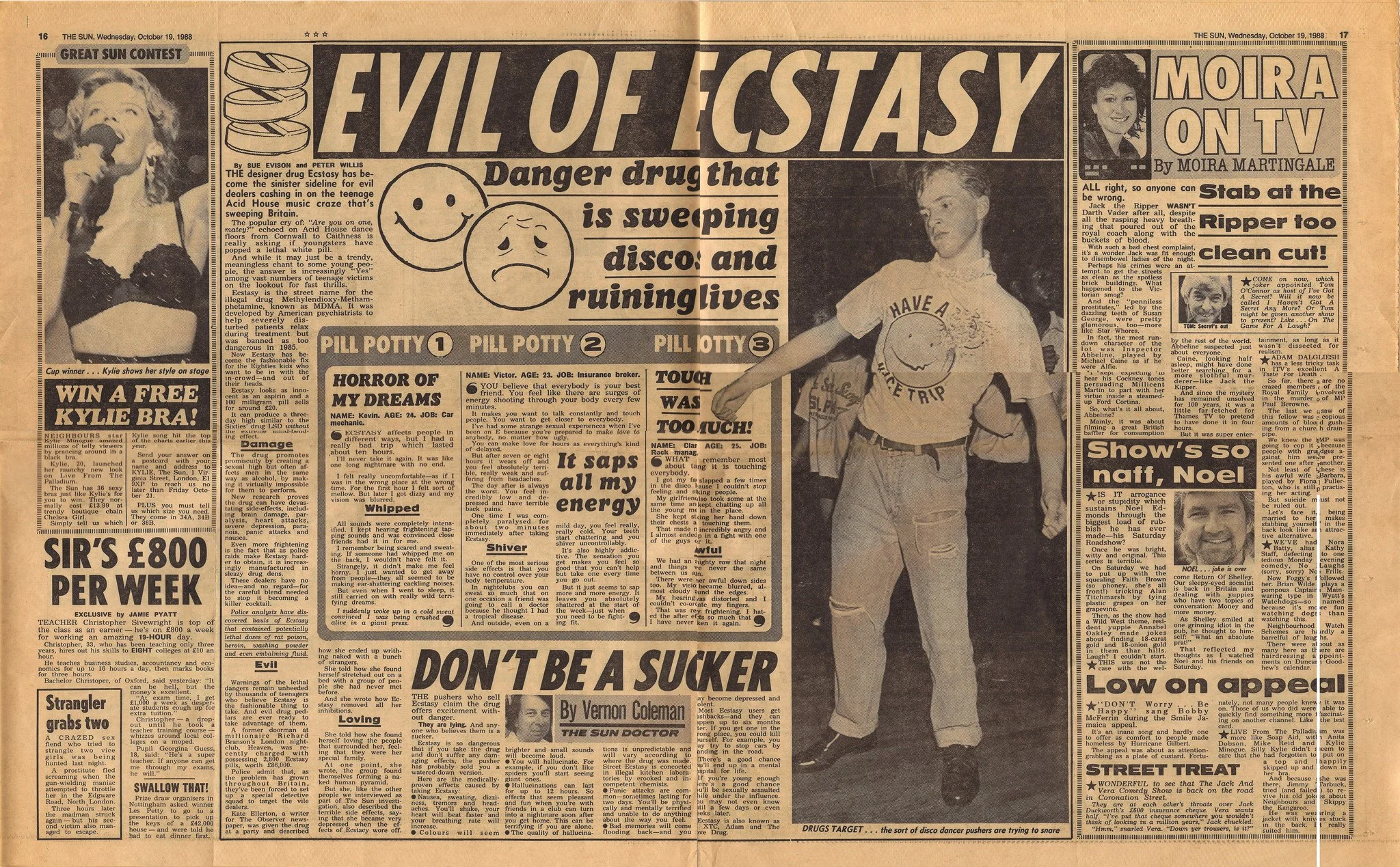

This is the legal context, then, that framed and threatened the enjoyment of Norfolk raves in unlicensed locations by the time I was attending them in the early 2000s – a context that also added to the sense of togetherness that they engendered. However, alongside the criminalisation of noise and the appropriation of space, the proliferation of illegal drugs at raves gained the most significant media attention in the late-1980s and early 1990s in tabloid newspapers like The Sun and The Mirror.[20] The safety of Ecstasy came under particular scrutiny after the death of a teenage girl at Manchester’s Haçienda nightclub in 1989, as did the behaviour of loved-up clubbers and ravers who were presented as perverse, self-destructive, and antisocial folk devils. Much of this was ill-informed scaremongering, although the optimism with which UK rave was initially associated was nonetheless giving way to darker ‘hardcore’ by the early ‘90s, which seemed to anticipate or reflect something of the post-rave comedown. An account of the darker side of the chemical generation has been documented by Simon Reynolds, whose survey of rave’s more nihilistic manifestations as well as its more aggressive and macho offshoots makes for disturbing reading.[21]

Fig. 8: Newspaper clipping from The Sun, 19 October 1988, pp. 16-17.

Nonetheless, around the same time that the social and pharmacological effects of Ecstasy were being condemned and ridiculed in the red-top press, influential members of the Francophone intellectual establishment were exploring more sanitised concepts of ecstasy in their theories of postmodern identity, culture and society. For instance, here’s Jean Baudrillard:

Ecstasy is that quality specific to each body that spirals in on itself until it has lost all meaning, and thus radiates on pure and empty form. Fashion is the ecstasy of the beautiful: the pure and empty form of a spiralling aesthetics. Simulation is the ecstasy of the real.

Baudrillard is not talking about MDMA, although it is telling that Steve Redhead opens his path-breaking study of the UK rave scene with this quote.[22] What prompted me to cite it is just how closely Baudrillard’s thinking around the concept of ecstasy tracks with hyper-refined decadent style in the nineteenth-century, where decadence was understood by its critics to spiral in on itself ‘until it has lost all meaning’, thus radiating ‘pure and empty form’. Also, the wonderful observation that ‘[f]ashion is the ecstasy of the beautiful’ might just as well have been plucked from the pages of Charles Baudelaire, or any number of decadent writers inspired by his work. Perhaps, too, we might think of artificial paradise – such as the domain crafted by Jean des Esseintes in Huysmans’s À rebours (1884) – as ‘the ecstasy of the real’.

I am intrigued by the possibilities that Baudrillard’s writing on ecstasy opens for those with an interest in decadence, but I also find it difficult to align the vacuity and meaninglessness that he associates with ecstasy with the kind of decadence that I’ve been exploring in this post. Ravers who dance in pursuit of collective euphoria invite us to attend to decadence as an experience rich with meaningfulness and profundity. The transient experience of that profundity is not a sign of vacuousness; rather, as many have argued before me, it is a crucial part of the countercultural power of raves as spaces that thrive on their temporary suspension of dominant tastes, conventions, and the law, especially when strategies are pursued that seek to undermine legislation like the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act.[23] Transience is what distinguished these raves from the legitimated clubs that spawned them, it held the key to their sustainability by popping up temporarily but perennially despite criminalisation, and it formed the basis of their effervescent profundity.

Fig. 9: Tekscape, 'Dust Tek', Manchester, May 2008. Photo by Molly Macindoe.

Alongside their political significances, residing at the crux of a cultural-political interface, these raves also invite us to reconsider the association of decadence with social atomisation. The attainment of euphoria while dancing in a crowd is often the consequence of recognising that one is in a crowd, and being entrained and entwined with that crowd and the music that holds sway over its pulsations and movements. Attention is preoccupied with interior sensations, but attention also reaches outward, searchingly, reciprocally, toward a gathered group. This inflects what we might call ‘euphoric decadence’ with a sociality that is so often disassociated from the horizons of decadence as a concept. It is that sociality that holds open an intriguing window for a politics of decadence that also, very often, has been denied it: a kind of politics that need not be connected to an explicitly activist project – although such projects do exist[24] – but that instead holds on to transient moments of countercultural pleasure as experiences rich with social, cultural and political significance.

Fig. 10: Hardcore Equals Freedom, UK Tek, North Witham Airfield (a.k.a Twford Wood), South Kesteven, Lincolnshire. May 22-23, 2015. Photo by Molly Macindoe.

Attempting to ‘transcend’ the concerns and realities of the everyday is not without issue. As explored above, Norfolk raves in the early 2000s both incorporated and elided the grounding of electronic dance music culture in the underground parties as well as the clubs and bars that welcomed gay African American and Latin American communities in New York and Chicago in the 1970s and 1980s. With hindsight, the transposition of this heritage into what was, at the time, a predominantly white county reads as appropriation. But as the scene evolves, as demographics and communities grow and change in rural areas, so too does the potential for a more inclusive and respectful culture in those areas. Here, perhaps, the rave becomes a site for fostering not just countercultural pleasure, lifestyle and community, but cross-cultural learning from marginalised communities as well.

Rave, in short, has furnished us with a compelling manifestation of countercultural decadence at the turn of our most recent century. That decadence may seem a world away from the excessive and perverted refinement that characterised decadences associated with late-Victorian and post-Victorian literature, but alternative countercultural manifestations in more recent years have also been crafted and refined to points of excess in ways that pull the establishment of ‘good’, ‘bad’ and even ‘dangerous’ taste into the foreground: a dissenting taste, perhaps, that revels in the ‘dis’ of distastefulness. Pathologised and criminalised, rich with the hyper-refined nuancing of style and genre, and operating in the cast-offs and interstices of postindustrial capitalism, or eluding them altogether in rural netherworlds, raves and ravers, I argue, invite us to appreciate decadence afresh: not as that held at a tantalising distance, but as that which might be embodied, enacted, and lived – if only, and always, for a moment.

Fig. 11: Ministry of Defence sandpit quarry, Bodney Camp, Watton, Norfolk, 2007. Photo by Holly Mabee, courtesy of Louise Render.

Acknowledgments

Tim Lawrence offered valuable feedback on this post, for which I’m extremely grateful. Thanks also to my cousin and fellow traveller Kirsty Alston for putting me in touch with Louise Render, who offered valuable curatorial and crediting support, and to Molly Macindoe and Holly Mabee for sharing an incredible range of photos, not all of which could be included here. Some of Molly’s photographs included in this post have been published in her book Out of Order, which meticulously documents the free party and teknival scene in the UK and across Europe. For more on Molly’s work, check out: www.mollymacindoe.com, @mollymacindoe (Instagram), @mollymacindoephotography (Facebook), @mollymacindoe (Twitter), and #OutOfOrderPhotobook.

Notes

[1] ‘Neo-Victorian Decadence’ took place at the Università degli Studi G. d'Annunzio in Chieti, Italy, 26-28 October 2022. It was co-organised by Il Centro Universitario di Studi Vittoriani e Edoardiani (CUSVE) at UDA, and the Decadence Research Centre at Goldsmiths, University of London

[2] Kristin Mahoney offers an instructive introduction to post-Victorian literature, which refers to literature that reinvigorates the interests and preoccupations of those living in the ‘yellow nineties’ from a position of critical distance. Kristin Mahoney, Literature and the Politics of Post-Victorian Decadence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), p. 3.

[3] Matthew Potolsky both identifies and challenges the association of decadence with social atomisation. See Matthew Potolsky, The Decadent Republic of Letters: Taste, Politics, and Cosmopolitan Community from Baudelaire to Beardsley (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

[4] Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, ed. & trans. Steven Corcoran (London: Continuum), p. 33.

[5] The opening of the Balearic-inspired Project Club on Streatham High Road in London is a notable example to highlight, which was set up by Paul Oakenfold and Ian St Paul in 1987 after a trip to Ibiza. ‘Balearic’ initially referred to an approach to DJ-ing and clubbing that was in ‘revolt against style codes and the tyranny of tastefulness’ then dominant in London clubs at the time, although Oakenfold’s acid house music went on to inspire a tranche of imitators, and loose-fitting beach-ware associated with Ibiza as a predominantly white tourist resort became closely associated with acid house audiences. See Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture, new ed. (Basingstoke and Oxford: Picador, 2008), p. 36. Note that acid house actually emerged from the pioneering work of Black producers and collectives in Chicago before it came to be associated with the largely white and touristic influence of Ibiza on the London club scene. Its emergence is closely linked to Phuture’s ‘Acid Tracks’ (1987), which was produced by Marshall Jefferson with Trax Records.

[6] William Rees, ‘“Le Freak, c’est Chic”: Decadence and Disco’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 3 (2) (2021), pp. 126-42 (p. 126). For an instructive overview of the civic state of New York in the 1970s, see Hillary Miller, Drop Dead: Performance in Crisis, 1970s New York (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2016). Compare this image of New York as being in a state of terminal decline with that depicted in the epilogue to Tim Lawrence’s book Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 433-42.

[7] I am grateful to Tim Lawrence for an instructive email exchange in which he clarified and nuanced the complexity of the dance party scene and its impact on the emergence of disco in the 1970s.

[8] See Walter Hughes, ‘In the Empire of the Beat: Discipline and Disco’, in Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose (eds), Microphone Fiends: Youth Music & Youth Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), pp. 147-57 (p. 147). Tim Lawrence also offers one of the most authoritative studies of the disco scene, problematising the relationship between its homophobic dismissal and the lived realities of its enjoyment among gay men. See Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, pp. 423-24.

[9] Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson, Discographies: Dance music, culture and the politics of sound (London and New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 73.

[10] Graham St John links these cultures to the sound system set-ups associated with Jamaican breakbeat, dub-reggae and dance hall. Only later did these scenes elide with punk, traveller and techno influences. See Graham St John, Technomad: Global Raving Countercultures (London and Oakville: Equinox, 2009), pp. 28-30.

[11] For instance, one of the raves I mentioned above, Planet Yes, rents out its speaker system for various licensed events through its sibling company Innerfield. Several of those in my own close and extended social group at the time were also involved with the running of a tent at Glastonbury, with others having since set up their own ticketed music festivals in Norfolk.

[12] See George McKay, Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties (London and New York: 1996), pp. 34-44 (p. 36).

[13] Gilbert and Pearson, Discographies, p. 30.

[14] Graham Bright, ‘Orders of the Day — Entertainments (Increased Penalties) Bill’, House of Commons, 9 March 1990, https://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=1990-03-09a.1110.0&s, accessed 12 October 2022.

[15] The 1982 Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act and the 1963 London Government Act ensured local authorities had the power to license and control places used for music and dancing. Other relevant legislation includes the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act, and the 1986 Public Order Act. Common Law also granted the police powers to prevent breach of the peace and public nuisance, which includes the endangerment of life and property, and warranted up to five years imprisonment.

[16] Bright, ‘Orders of the Day’.

[17] McKay, Senseless Acts of Beauty, p. 119.

[18] Gov.uk, ‘Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994’, UK Public General Acts, c. 33, Part V, Section 63 (1994), accessed 6 December 2021. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1994/33/section/63#:~:text=S,-(1)This%20section&text=intermissions)%3B%20and-,(b)%E2%80%9Cmusic%E2%80%9D%20includes%20sounds%20wholly%20or%20predominantly%20characterised,a%20succession%20of%20repetitive%20beats.

[19] See Caroline Steadman, ‘An introduction to the rave, teknival and free party scene’, in Molly Macindoe, Out of Order: The Underground Rave Scene 1997-2006 (n.c.: Front Left Books, 2015), pp. 446-50 (pp. 448-49).

[20] See, for instance, Sue Evision and Peter Willis, ‘EVIL OF ECSTASY: Danger drug that is sweeping discos and ruining lives’, The Sun, 19 Oct. 1988, pp. 16-17. The feature also includes an article Vernon Coleman titled ‘DON’T BE A SUCKER’. Given the feature’s contextualisation in light of post-‘70s disco, it is hard not to read this as a coded homophobic slur.

[21] Reynolds, ‘Slipping into Darkness: The UK Rave Dream turns to Nightmare’, in Energy Flash, pp. 188-202 (p. 201 and p. 258).

[22] Steve Redhead, ‘The Politics of Ecstasy’, in Steve Redhead (ed), Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture (Aldershot: Avebury, 1993), pp. 7-27 (p. 7).

[23] The work of Hakim Bey is regularly cited in literature on the rave scene. See Hakim Bey, T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, 2nd ed. (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2003).

[24] See, for instance, adrienne maree brown, ‘Introduction’, in Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, ed. adrienne maree brown (Chico and Edinburgh: AK Press, 2019), pp. 3-18.