Dancing Decadence: Disco-mania

Dr Adam Alston – Goldsmiths, University of London

It’s 5am and revelers are aglow, their insides throbbing with thumping techno. We’re at a club called The Pickle Factory in London’s Cambridge Heath, which has been taken over by an itinerant night called Boudica: ‘a London based label and party exploring the darker and hedonistic side of electronic music, run by women and non-binary folk’.[1] This is the first night out that most of those in attendance have been able to enjoy for some time, as it’s taking place shortly after the re-opening of nightclubs in the city after government coronavirus restrictions were lifted on 19 July 2021. I feel a familiar sensation as I move to the music: a delirious joy – an ecstatic pleasure – and the movements and the glances and the smiles of those around me suggest that I am not alone. The feeling is contagious, as is the urge to dance.

Boudica was launched by the Italian, London-based DJ and producer Samantha Togni in 2019, before suspending its in-person events the following year in line with government coronavirus restrictions. This night was its re-launch, and featured Togni, Tasha, MarcelDune, Anabel Arroyo, SØRAYA, and Lewis G. Burton (founder of another queer and trans-inclusive club night called INFERNO) on its bill. Many of the attendees were dressed in fetish gear – which is to say, in clothing and makeup that was spectacular and alluring inside the club, part of what performance scholar Marcus Bell describes as a ‘socio-aesthetics of the night’, but that might also put them at risk in everyday spaces.[2] Each participated in the formation of a transient communitas of a kind that enables and nurtures relationships and desires that do not fit so neatly within normative spaces and chronologies.

This post is inspired by Boudica, and is the latest in a series of posts on this blog that I’ve been gathering under the title ‘Dancing Decadence’. However, its focus has changed quite considerably after reflecting on the issues and questions that bind the posts in this series together, most notably an expansive set of connections between contagion, sociality, and the urge to dance, as well as the spectacle of the dancing body. How have dancing bodies been pathologised, criminalised, and derided as a pathogen? How has contagion been choreographed on dancefloors and stages, and what anxieties and fears, pleasures and desires, do these choreographies arouse?

While tempting to dwell on the epidemiological context of the pandemic, it soon became clear that these questions invite a capacious response that recognises contagion not just as a biomedical phenomenon, but a cultural phenomenon with an important heritage. Narratives of contagion have a habit of sticking to particular kinds of body, desire and pleasure, often in ways that have little – if anything – to do with biomedical contagion, especially when the fleshiness of the dancing body is taken into account. For instance, as Togni explores, it’s important to account for the sanctuary that queer-friendly nightclubs can provide for those whose appearances and sexual orientations have been routinely subject to narratives of contagion and pollution.[3] Gender, sexuality and race become entangled in the identification of the dancing body as an infectious pathogen, which informs and shapes their reception in theatres and club spaces, as well as the journalistic media that attends to them.

One of the most important contexts for attending to this entanglement, it seems to me, is the underground emergence of disco in the 1970s, its absorption into the cultural and leisure industries, and its subsequent derision as a ‘decadent’ form of music and cultural practice that was seen by the cultural elite as well as conservative commentators at the time to have a ‘decadent’ – i.e. debilitating – impact on music, dance culture, and society. This is why I’ll be returning to the disco scene in New York in the 1970s as a time and a place when dancing bodies in nightclubs were subject to derision and moral judgements about an emerging ‘mania’ for disco as a genre and dance culture, building on ideas set out in an earlier post on rave culture. Key to this discourse was a rhetoric of decadence that cut across the political spectrum: on the one hand coming from elite music aficionados who were worried about the reproduction of popular music formulas that served the ‘decadence’ of a leisure industry, and on the other from conservative commentators who were worried about cultural and sexual practices that were seen to accompany this ‘mania’, especially drug misuse, the erosion of a work ethic as dancers prioritised night life over working life, and a perceived lack of sexual propriety on dance floors. However, rather than disregarding the relevance or importance of decadence as a frame for understanding dance music culture, I am more interested in what it might mean for this term – so laden with the condemnation of non-conformity – to be reclaimed and celebrated. What might it mean to recognise ‘Disco-mania’ as a decadent practice based on the enjoyment and cultivation of pleasures that others deem to be illicit, distasteful, or socially and morally corrosive? What can this tell us about cultural politics, and how values and propriety come to be established as such?

An important sense of the word ‘decadence’ means ‘to fall down or away’, or ‘decay’ (from the Latin decadēre). The conjunction of this specific meaning with the more popular sense of decadence connoting some kind of hedonism generally characterises condemnatory usages of the word. However, in being condemned as contagiously decadent, the dancing bodies addressed in this post were also recognised as agents of social and cultural transformation. What interests me most are the spaces between this agency and its being pathologised or derided: spaces that serve as resistant platforms for experiencing pleasure and desire, each giving rise to contagious choreographies that serve as vectors of socio-cultural transmission. Ultimately, I’ll be arguing that Disco-mania – particularly at the point of its emergence, and among very specific communities of stakeholders – formed the basis of a liberatory sociality and eroticism, and that nights like Boudica still keep this extraordinary flame alight.

*

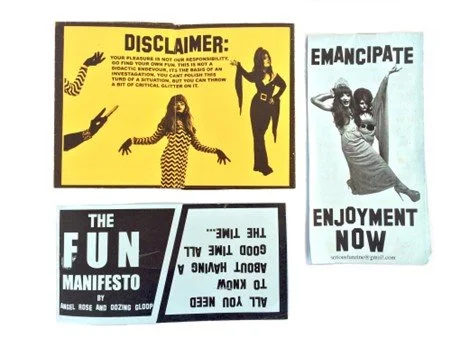

For artists and performers Oozing Gloop and Angel Rose, the pleasures and excesses of ecstatic dance in nightclubs and appropriated spaces can produce a feeling – even if it is just a feeling – of transcendence, or what Rose calls ‘Transcendance’ in a short essay dedicated to ‘party power’.[4] It appears in the first instalment of Gloop and Rose’s zine series Serious Fun – The Serious Fun Funzine (2014), and builds on what they describe as ‘4 years of intensive field research at nightclubs and after-parties’, having ‘swum the sublime sewers of London, intoxicated by the stench of excitement’.[5] For Gloop and Rose, ‘[f]un is both a means and an end, journey and destination, pleasure and purpose, material, tool, idea, attitude, and culture […]. Fun is not something we can ever articulate in advance, but a moment where whatever we might be doing is discursively reconstituted as “fun”’.[6] This understanding of fun and its expression in Transcendance is not based on the realisation of a particular outcome other than fun and the expenditure of energy in the company of others, and it is not something that can be stored and accumulated. Its transience is not so easily commodified, although the experience economy is ever-alert to the commodification of fun, nightclubs included. Moreover, experiencing fun and Transcendance on nightclub dancefloors is far from an insular and myopic affair. Its pleasures are closely connected to sociality, and the bringing together of friends and strangers in communal moments of release.

Fig. 1: Serious Fun mini-zines (2014), written by Angel Rose and Oozing Gloop, and designed by Rose. Courtesy of Angel Rose.

In Rose’s essay on party power, she draws a parallel between Transcendance and ‘manias’ for dancing, or ‘choreomania’. She writes:

Dancing mania was born out of times of hardship, and such performances allowed its ‘victims’ to exhibit behavior that was prohibited at any other time. This makes for an important parallel to the roots of 1970s disco, which can be found in the then-ghettoized cultures of black, Latino and gay America. On this comparison, the cultural and spiritual transgressions of medieval dance mania are kept alive in Disco-mania.[7]

As performance scholar Kélina Gotman notes, dancing manias, or ‘choreomania’, does not name a single phenomenon, but many, and is best understood as ‘a history of ideas about an epidemic disorder, a dancing plague, as it shifts across fields of knowledge and geographic terrains’.[8] Unlike neurodegenerative diseases, such as ‘Huntington’s chorea’, choreomania becomes disease-like in its transmission from one body to another, be it outbreaks of ‘dancing plagues’ that cause groups of people to dance uncontrollably in private or in public for days or weeks at a time, or ‘manias’ for choreographic fashion (as I’ve explored in an earlier post). Of particular note is how civil authorities sought to contain the ‘excess vitality’ of choreomaniacal outbreaks, or what Gotman describes as ‘a hyperbolic, feminine, and queer sort of expansive gesturality spilling beyond the individual body into public space’.[9]

Dancing plagues speak to numerous historical and cultural contexts ranging from the inducement of Tarantism in medieval Italy (a response to spider bites from which the Tarantella is said to derive), to the 1863 Madagascan imanenjana, which found its victims taking over the streets and dancing to a point of exhaustion ‘as if possessed by some evil spirit’.[10] In the majority of cases, what results is a kind of feverish trance. The first recorded choreomaniacal epidemic in 1374 extended ‘from the foot of the Alps down through the Rhine Valley to modern-day Belgium’, although an outbreak in Strasbourg in mid-July of 1518 is better-documented.[11] In an uncanny inversion of the lockdown conditions experienced by people all over the world during the coronavirus pandemic, the Strasbourg municipality requisitioned public spaces in guildhalls and marketplaces to contain the feverish dancers and to limit the apparent death count. Around fifteen victims each day were said to be claimed by the disease in Strasbourg, although the actual toll remains elusive,[12] and it took just shy of a month for the outbreak to clear, and only then, we are led to believe, as a consequence of penance and pilgrimage to the local shrine of St. Vitus (incidentally the Strasbourg outbreak has gained renewed attention since the pandemic – see, for instance, Gareth Brookes’ graphic novel The Dancing Plague (2021), and Florence and the Machine’s fifth studio album Dance Fever (2022)).

Vid. 1: Florence + The Machine, Dance Fever (2022).

The dancing body was believed to be symptomatic of demonic possession in these European examples, and an expression of evil to which women were especially susceptible: an evil with a malign influence not just on personal autonomy, but the stability of patriarchal communities as well. Each of these examples may well have resulted in ‘a decidedly conservative resolution that reaffirmed the heretofore-uncertain authority of the old order’;[13] however, as Gotman recognises, they also reveal ‘a fantasy of orderliness’ upon which the disciplining of disorderly bodies is built.[14]

This is where Rose’s thinking around Disco-mania comes in, which we might read as a compulsive desire to enjoy the excesses of dancing with abandonment as practised among disenfranchised communities that are seen, by their critics, to threaten ‘a fantasy of orderliness’. However, unlike medieval dancing plagues, the enjoyment of Disco-mania is both fun, and has a decadent edge. As William Rees observes in an illuminating study of the ‘decadence’ of disco: ‘[t]he optimistic beats of 1970s and 1980s disco might seem a strange comparison to the decadent tradition’s obsession with rot’; however, ‘decadent legacies’ and qualities are there to be found in the history of disco.[15] For instance, Rees highlights the prevalence of dandyism in both decadence and disco, as well as comparable narratives that regarded and positioned them as representing or being symptomatic of moral and social decline (which says more about the prejudices of those identifying the decline than it does about the lived realities and experiences of those immersed in these cultures). I will be unpicking the last of these observations most closely in what follows.

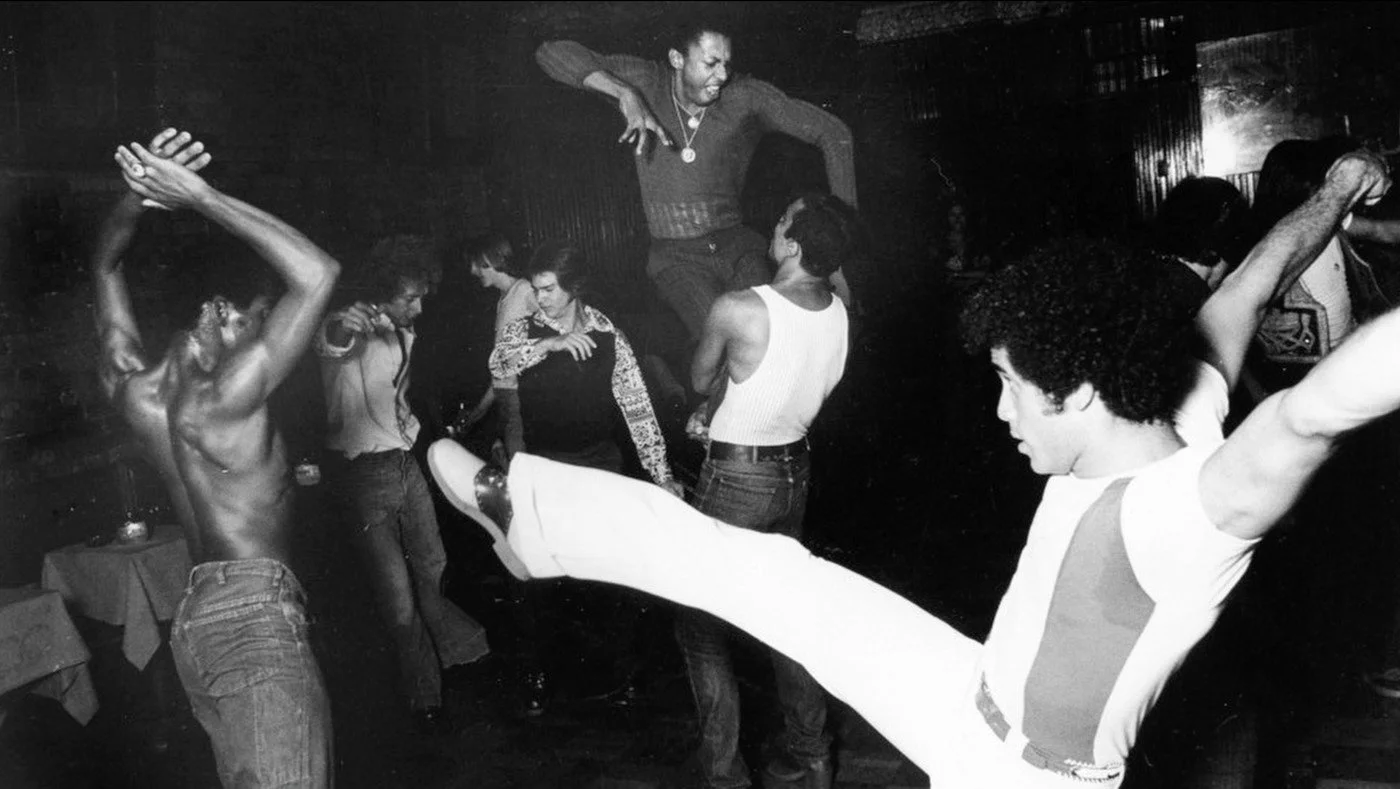

Discothèques were a French invention imported to the US with the opening of Le Club in New York on New Year’s Eve 1962. Disco was not to coalesce into a recognisable genre of music until 1973,[16] although an underground dance party culture that has since been associated with disco can be traced back to David Mancuso’s first DJ-led countercultural Loft party in downtown Manhattan in 1970, which built on happenings and parties he had been organising since the 1960s after attending Timothy Leary’s lectures and private parties (the title Mancuso gave to the party, Love Saves the Day, is a thinly-veiled reference to the drug that made Leary famous). These parties were gay-friendly, although the Loft was not a gay venue per se, and it drew a mixed crowd. The Loft was just as significant because of the fact that it welcomed gay Black and Brown communities in addition to a straight white clientele. The Sanctuary in Hell’s Kitchen was another venue that attracted a mixed crowd, although it was initially set up as a straight venue in 1969, and was only later identified as ‘one of the first flamboyantly gay dance clubs in the city’, and as ‘a temple to joyous decadence’.[17] ‘Decadence’ in the superficial sense of it referring to vacuous glitziness and elite hedonism might be associated more readily with clubs like Studio 54, which opened in downtown Manhattan in 1977 amid a lucrative storm of media and celebrity attention. However, once the subversive sense of decadence as connoting some kind of dissonant pleasure is taken into consideration, pleasures and modes of sociality that prudish or reactionary critics might find distasteful, self-destructive or socially-destructive, then the political significances of raising ‘a temple to joyous decadence’ come into view in a context that predates its absorption into more straight-centric and high-profile venues.

Downtown and midtown venues like the Loft and the Sanctuary had a formative role to play in establishing 1970s dance party culture, and in precipitating the disco scene that followed their emergence. Their relatively underground but open entrance policy also provided important havens for gay Latin and African American revellers who may have been put off by more mainstream, straight and predominantly white venues. However, the Latin and African American roots of disco stretch much deeper. Firstly, venues like the Loft and the Sanctuary find precedent in East Harlem rent parties playing non-stop soul that welcomed straight and gay African Americans in the 1960s. Secondly, African and African American musicians have made some of the most important contributions to the genre. The Cameroonian musician and songwriter Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’ (1972) was one of the first records to be associated with disco (Aletti 1973, 60), and Sylvester’s ‘You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)’ (1978) is widely recognised today as one of the most iconic anthems of the period. Also, as Reynaldo Anderson recognises, Sylvester may have ‘personified the excesses of the 1970s’, but they also ‘emerged in the wake of a confluence of forces that would shape popular music and culture for the remainder of the twentieth century’, including ‘the civil rights movement, the emerging women’s movement and gay liberation movement’.[18] Thirdly, disco finds roots in other genres pioneered by African Americans, including Motown, blues, R&B and gospel, and its earliest innovators looked to ‘influence the energy and erotic expression of dancers in nightclubs that catered to African Americans, gays, Latinos and others’.[19] Fourthly, some of the earliest New York disco DJs integrated African and Latin recordings in their sets, although the co-optation of these sounds became detached from their international roots.[20] Finally, disco music and the cultures surrounding it metamorphosed with its global dispersal from the mid-1970s, where disco took on different forms, meanings, and functions in countries as diverse as Brazil, China, India, Japan, Lebanon, and Nigeria.[21] In other words, gay and diasporic experimentation and community-driven practice both anticipates and contributed to the evolution of disco from underground dance parties into a coherent genre with international reach.

Vid. 2: Manu Dibango’s Soul Makossa (1972) .

The capitalistic qualities of disco in its more popular iterations played into the elitist derision of disco as ‘decadent’, particularly its polished production in recording studios and frequent reliance on performer-commodities, as well as the kitsch sumptuousness and gaudy materialism of commercial discos themselves. The glitziness of elite clubs like Studio 54 is a case in point, but more was being attacked in this hostility than the commercial orientation of a once underground and experimental scene. Communities that were marginalised, erased and oppressed in mainstream society and culture fed into the derision of disco as ‘decadent’, ‘superficial’ and a ‘dreaded musical disease’ toward the end of the 1970s.[22] Pejorative references to disco’s superficiality and dreaded contagiousness was to deride more than its capitalistic associations, then. Such derision employs a lexicon that is both homophobic and racist once read in light disco’s roots in Latin and African American subculture, especially gay subculture.

Derision is one thing, elision another. John Badham’s well-known film Saturday Night Fever (1977) highlighted the working-class alter-ego of the more elitist and exclusive disco scene associated with Studio 54.[23] However, as Walter Hughes observes, the film also makes an ‘overdetermined attempt to heterosexualise disco by showing that white working-class males who harass homosexuals and rape women could dance to it, as long as it was performed not by the African American divas preferred by gay men, but by a trio of Australian falsetto’.[24] The side-lining of disco’s relationship to the gay underground is all the more egregious given the film’s title, which foreshadows another kind of ‘night fever’ that prompted Republican commentators and senators to deride queer art and culture as ‘decadent’ during the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s.[25] The AIDS epidemic was a time not just of epidemiological crisis, but moral panic about the ‘decadence’ of countercultural proclivities that stretches back to the 1960s and 1970s, from which disco’s championing of self-fulfilment, sexual liberation, bodily pleasure, multiculturalism, and nonnuclear families, as the music historian Tim Lawrence observes, ‘could hardly be disentangled’.[26]

Fig. 2: ‘Disco music at the Loft’. Still from I Was There When House Took Over The World (2017), dir. Jake Sumner for Channel 4.

The AIDS crisis forms an important backdrop that underpinned the evolution of disco and dance music culture into a more diverse range of genres and subgenres. Chief among the musical and cultural bridges between disco and its derivations in the 1980s are the Chicago house and acid house scenes, much more so than the other two ‘pillars’ of electronic dance music – Detroit techno and New York garage – as house music was initially grounded in gay, Black and Brown subcultural dance practice in ways that echo the early development of dance party culture in New York. As Terre Thaemlitz (aka DJ Sprinkles) insists, house music is a product of queer and transgendered subculture in the 1980s and 1990s, including dance floors at clubs like Sally’s II in New York, which attracted Latinx and African American trans sex workers as much as their johns from the West side piers – another kind of space that became closely associated with voguing, cruising, and gay and transgendered sex work at the height of the AIDS crisis.[27] Also, as José Esteban Muñoz writes in his Conclusion to Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009), ecstatic experience on nightclub dance floors may well have involved ‘a stepping out of time and place’ for fans of electronic dance music at the time, as it does today, but the time and place that is stepped out of has different ramifications for members of Black, Brown and queer communities, for whom the times and places of capitalism and heteronormativity are saturated ‘with violence both visceral and emotional’.[28] Muñoz is appealing here to a wide range of readers, but especially queer readers, not least those doubly marked and disenfranchised as a consequence of their queerness and race.

Muñoz may well have agreed with adrienne maree brown’s insistence ‘that we all need and deserve pleasure [… but] we must [also] prioritize the pleasure of those most impacted by oppression’[29] – not least if Transcendance and Disco-mania are to avoid conflation with the excesses made exclusively available to those privileged by wealth, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and whiteness. This is what makes Togni’s work with Boudica so important, alongside other relevant platforms founded by the likes of Lewis G. Burton (Inferno) and Xilhu Ayebaitari Ese, aka DJ Ayebaitari (Queer Rave), which enable revellers – especially disenfranchised and marginalised revellers – to ‘experience ecstatic dance […] in a space filled with love, creativity, freedom, queerness, diversity and safety’, as Ayebaitari puts it.[30] They are actively honouring a legacy that positions the early house music scene as a vector of transmission, an interface, between disco and the queer-friendly dance music cultures it spawned. Pejorative decadence weaves in and out of that heritage, haunting it, but also stimulating the formation of spaces and communities that persist in the face of ostracism and danger, not least in the aftermath of AIDS, its manipulation in the political sphere, and its subsequent mitigation (for instance, as pre-exposure prophylaxis became more widely available).

Decadence ghosts the heritage of the dance music cultures discussed in this post, but it is not the decadence of fin de siècle Europe; it is a decadence overshadowed by prejudice specific to the contexts in which these scenes emerged, including the ways in which seminal dance music cultures have been dismissed and derided, the homophobic and racist fears and anxieties associated with specific diasporic and gay communities, and the ways in which dance music venues can function as sanctuaries, as ‘temple[s] to joyous decadence’, for those marginalised within or threatened by more mainstream dance culture. This is why any embrace of Transcendance and Disco-mania as ‘decadent’ needs to be read not merely in terms of how they foster interstices conducive to the subversion or transgression of norms or laws, or in their being seen and labelled as a symptom of social decline. Rather, they are grounded in specific cultures of persecution and resistance.

Framing the ‘infectious rhythms’ of disco as ‘mania’ also needs to be read alongside white supremacist notions inherited from the nineteenth century that fixated on the pathologisation of regressive, unruly and primal ‘symptoms’, especially with regard to improvisatory choreographies on the dance floor.[31] The dancers explored in this section, as well as the music of pop icons like Manu Dibango and Sylvester, exposed the apparent naturalness and intractability of a culture’s organisation around a unified set of mores and institutions for what it was: which is to say, a ruse. Their interventions neither began from a position of appropriating Orientalist style, nor did they play to anxieties about the corruption of the pure white body, as explored in the previous sections. Instead, theirs was a more insurgent attempt to recuperate power from racist and homophobic influences and tendencies in popular culture.

In sum, the accusations of decadence and related concepts that plagued disco need to be read alongside the sanctuary that an alternative and underground dance scene offered to marginalised and disenfranchised revellers. The dance cultures they fostered displaced the insular and narcissistic individualism with which decadence is so often associated in popular culture. In the contexts explored in this section, decadence and its ecstatic pleasures are emphatically communal. Nonetheless, without acknowledging the ways in which those most marginalised within a dominant culture are also threatened by that culture’s evolution – for instance, when the mainstream appropriates a countercultural or underground practice, or derides its development as ‘superficial’, ‘diseased’, ‘unnatural’, and ‘decadent’ – then rose-tinted utopianism is likely to overshadow the lived realities of appropriation and changing patterns of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste.

The emergence of disco in the 1970s and the house music scene in the 1980s drew a broad range of communities, but the contributions of racially and sexually disenfranchised communities were significant in the establishment and development of both as coherent genres and cultures. The mainstreaming of these countercultural and subcultural scenes both drew upon and elided the formative contributions of under- and misrepresented demographics. These contributions have also fallen foul of resentment and hostility: for instance, in deriding disco as a ‘deadly musical disease’, and the people who dance at them – especially its gay pioneers – as ‘decadent’ and ‘unnatural’. The backdrop of the AIDS crisis also cannot be extricated from the emergence of the house music scene, or the ways in which the AIDS crisis was conflated with a broad range of underground and subcultural activity at the time.

The ‘decadence’ of the dance cultures explored in this post relates to both the terms of their derision, and the modes of their reclamation. The latter, especially, is suggestive of a need to move beyond the term’s limiting associations with material wealth and narcissistic individualism. The fabulous luxuries and ecstatic abundance enjoyed in conditions of relative deprivation are suggestive of an oppositional quality that is resistant to the hoarding of wealth. Moreover, the generation of ecstatic communitas on the nightclub dancefloor can play a key role in ensuring the resilience and in some cases the survival of disenfranchised social groups in racist and homophobic societies: a far cry, in other words, from the atomisation that tends to characterise configurations of decadence inherited from fin-de-siècle Europe. As such, we would do well to reimagine who decadence is for, and who has played a role in its evolution as a term of condemnation and liberation alongside its framing as an embodied and enacted practice. This is why I make the case that subjects marginalised and held hostage by a society for their illicit commitments to dance hold a compelling key to understanding the power and potential of decadence today, not least at a time when we are able to dance together again in the wake of a devastating pandemic.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dan O’Gorman and Alexandra Kolb for offering comments on an early version of this post, and to Tim Lawrence, whose email correspondence had a formative impact on my thinking around disco, house, and dance music.

Notes

[1] Boudica, ‘Boudica: Tasha, Samantha Togni, Lewis G Burton, MarcelDune, Anabel Arroyo, SØRAYA’, The Pickle Factory, 24 July 2021, https://ra.co/events/1443287, accessed 24 February 2023.

[2] Marcus Bell, ‘INFERNO: Catastrophically Queer’, Agôn (9) (2021), pp. 1-19 (p. 5).

[3] Samantha Togni, ‘Creating a Space for Lockdowns’ Lost WomXn Led Nightlife Scene’, Thiiird Magazine, 13 November 2020, https://www.thiiirdmagazine.co.uk/stories/creating-a-space-of-care-for-lockdowns-lost-womxn-lead-nightlife-scene, accessed 24 February 2023.

[4] Angel Rose, ‘Party Power and Party Process’, in Oozing Gloop and Angel Rose, The Serious Fun Funzine (London: A. Rose and O. Gloop, 2014), pp. 45-53 (p. 47).

[5] Oozing Gloop and Angel Rose, The Serious Fun Funzine (London: A. Rose and O. Gloop, 2014), p. 4.

[6] Gloop and Rose, The Serious Fun Funzine, p. 5. See also Ben Walters, ‘Homemade Mutant Hope Machines’, PhD diss, Queen Mary, University of London, 2020, https://duckie.co.uk/media/documents/PhD%20ebook%20Dr%20Duckie.pdf, accessed 24 February 2023.

[7] Rose, ‘Party Power and Party Process’, p. 46.

[8] Kélina Gotman, Choreomania: Dance and Disorder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 4.

[9] Gotman, Choreomania, p. 6.

[10] Andrew Davidson, ‘Choreomania: An Historical Sketch, with Some Account of an Epidemic Observed in Madagascar’, Edinburgh Medical Journal 13 (1867), p. 131.

[11] Michael Lueger, ‘Dance and the Plague: Epidemic Choreomania and Artaud’, in The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Theater, edited by Nadine George-Graves (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 948-64 (p. 950).

[12] John Waller, The Dancing Plague: The Strange, True Story of an Extraordinary Illness (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2009), pp. 148-49.

[13] Lueger, ‘Dance and the Plague’, p. 960.

[14] Gotman, Choreomania, p. 17.

[15] William Rees, ‘“Le Freak, c’est Chic”: Decadence and Disco’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 3 (2) (2021), pp. 126-42 (p. 126).

[16] Vince Aletti, ‘Discotheque Rock ‘72 [sic]: Paaaaarty!’, Rolling Stone, 13 September 1973, p. 60.

[17] Matthew Collin, Altered state: The Story of Ecstasy Culture and Acid House, revised ed. (London: Serpant’s Tail, 2009), p. 6.

[18] Reynaldo Anderson, ‘Fabulous: Sylvester James, Black Queer Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic’, Dancecult 5 (2) (2013), https://dj.dancecult.net/index.php/dancecult/article/view/394/413, accessed 24 February 2023.

[19] Anderson, ‘Fabulous’; see also Tim Lawrence, Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture 1970-1979 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

[20] For examples, see Tim Lawrence, ‘Epilogue: Decolonising Disco – Counterculture, Postindustrial Creativity, the 1970s Dance Floor and Disco’, in Global Dance Cultures in the 1970s and 1980s: Disco Heterotopias, edited by Flora Pitrolo and Marko Zubak (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), pp. 303-38 (pp. 324-31).

[21] See Flora Pitrolo, and Marko Zubak, ‘Introduction: Disco Heterotopias – Other Places, Other Spaces, Other Lives’, in Pitrolo and Zubak, Global Dance Cultures, pp. 1-28 (p. 1).

[22] References to disco as a ‘superficial’ and ‘dreaded musical disease’ are documented by Tim Lawrence. Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, pp. 373-74. References to the ‘decadence’ and ‘unnaturalness’ of those attending disco are documented by Walter Hughes. Walter Hughes, ‘In the Empire of the Beat: Discipline and Disco’, in Microphone Friends: Youth Music & Youth Culture, edited by Andrew Ross and Tricia Rose (New York: Routledge, 1994), pp. 147-57 (p. 147). Note that Lawrence also problematises the impact of this homophobia on the night-to-night reality of disco culture in the late-1970s. See Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, pp. 423-24.

[23] For an instructive account of the relationships between disco and the working classes, see Jefferson Cowie Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York and London: The New Press, 2010).

[24] Hughes, ‘Empire of the Beat’, p. 147.

[25] Adam Alston, ‘Survival of the Sickest: On Decadence, Disease, and the Performing Body’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 4 (2) (2021), pp. 130-56.

[26] Lawrence, Love Saves the Day, p. 379.

[27] Alex Macpherson, ‘Deeper underground: FACT meets Terre Thaemlitz’, Fact Magazine, 29 April 2014, https://www.factmag.com/2014/04/29/deeper-underground-fact-meets-terre-thaemlitz-part-one/, accessed 24 February 2023. See also Fiona Anderson, Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York's Ruined Waterfront (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019); David Gere, How to Make Dances in an Epidemic: Tracking Choreography in the Age of AIDS (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004).

[28] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009), pp. 185-87.

[29] adrienne maree brown, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (Chico, CA, and Edinburgh: AK Press, 2019), p. 13.

[30] Xilhu Ayebaitari Ese, ‘DJ Ayebaitari on ecstatic dance and raving as ritual’, Rave Report, 7 December 2020, https://www.theravereport.com/blog/dj-ayebaitari, accessed 24 February 2023.

[31] I am borrowing the term ‘infectious rhythm’ from Barbara Browning, Infectious Rhythm: Metaphors of Contagion and the Spread of African Culture (New York and London: Routledge, 1998).