The Mythical Decadence of Weimar Cabaret

A Staging Decadence Long Read

Guest post: Professor Laurence Senelick, Tufts University

Say ‘Weimar cabaret’ to most people and their mind will immediately go to the Hollywood film of 1972. Based on a stage musical loosely begot by a play and movie begot by the Berlin stories of Christopher Isherwood, it was at several removes from lived reality, a fictional amalgam of pre-existing clichés. In particular, the cabaret of the title, the Kit Kat Klub, was made out of whole cloth: its individual features – the half-naked female orchestra, the demonic master of ceremonies, the brassy songs, the jazz-inflected melodies and the expatriate star – may have been on offer separately at different locales, but could not be found all in one place. And a cabaret with a mixed audience ranging from bohemians to drag queens to profiteers to tourists to Storm Troopers never existed. Berlin cabarets, like London music halls, appealed to and attracted specific groups; a clear distinction was made between those that offered eye candy and those that engaged the intellect.[1]

This ‘long read’ blog post argues that the decadence of Weimar cabaret has been grossly exaggerated, and that the common notion derives in large degree from Nazi propaganda, which in turn influenced the various avatars of the Broadway musical. The musical in its own turn has dominated and perpetuated the image of German cabaret in the 1920s and ‘30s.

The Cabaret

Decadence applied to Weimar cabaret is something of an oxymoron. ‘Decadent’ implies decline and fall, decrepitude and etiolation. The Weimar Republic, although beset with problems both inherited and of its own making, had just been born. The burgeoning population of Berlin had an exceptionally high proportion of youth, due in part to a spurt in the birth rate between 1900 and 1910 and in part to a loss of adult males in the Great War. ‘Jugend was becoming a code-word, implying the breakdown of traditional ties and social controls’. [2] Considering itself a lost generation, many young people rejected previous systems of morality and idealism, not so much a declension as an abstention from past ‘glories’.

As an art form the cabaret was also young, coming out of its teens during the Weimar years. Its intention was deliberately to épater le bourgeoisie; unorthodox behaviors and sexualities were frequently on display, but the vigor and potency of its performers and its material made it one of the most vital types of performance in the twentieth century. Conservatives and reactionaries may have found it ‘perverse’, but what might be denounced as decadence was in fact liberation from convention.

The cabaret artistique sprang up in the late 1880s in various European capitals as gatherings of poets and journalists in taverns to recite their writing aloud. Gradually, friends were invited to sit in, and soon the general public paid for the privilege. Even then, the styles differed: in Montmartre, the Chat Noir charmed its audience with courtly speeches, Gothic surroundings and whimsical shadow plays, while at the Mirliton its host Aristide Bruant insulted the spectators and sang slang-riddled ballads of lowlife.

Censorship barred direct political commentary from these early cabarets, but their general attitude was oppositional. As Groucho Marx sang in Horse Feathers (1932), ‘Whatever it is I’m against it’. At its most basic, the aesthetic of the early cabaret stood in protest to the official art of the nineteenth century: three-volume novels, grand opera, and academic painting were adjudged overblown and philistine. On the other hand, popular forms of entertainment – music hall, variety, circus, pantomime – were lively and appealing, made up of short-form attractions. Smoking, drinking, even solicitation for sex were tolerated, even encouraged. The cabaretic ideal was to cross-fertilise the vivacity and sensuality of the popular arts with the refinement and mental stimulation of the traditional arts.

In Germany, this manifesto was made explicit. The blowsy beauties who play the accompaniment in Cabaret the musical actually belong in the Tingel-Tangel, a low dive whose female personnel sat in a semi-circle on stage, awaiting their turn and providing a garishly lit equivalent of the brothel show-room. It is accurately reproduced in Josef von Sternberg’s film The Blue Angel, as an appropriate setting for Marlene Dietrich’s tawdry Lola-Lola. German variety shows were coarse and circus-like. To supersede this, propagandists, parodying Nietzsche, proposed an Ũberbrettl or Super-gaff that would offer witty verse, satiric sketches and sprightly music in a succession of short turns. A great many modernist talents, among them Frank Wedekind, Christian Morgenstern and Joachim Ringelnatz, channeled their energies into this new form. Hindered from dealing with current events, the satire was mostly directed at literary and theatrical trends; the tone ranged from nonsensical to macabre. Munich cabarets tended to be more intimate, bohemian and ‘edgy’, skirting the boundaries of the permissible; whereas Berlin cabarets were more good-natured and gemütlich. No matter the degree of antinomian aggression, experimentation with form was a constant. The cabaret came to serve as a congenial forum for expressionists, DADAists, and futurists.

Many of these efforts were short-lived. Economics was usually the reason the bill might be adapted to the broader tastes of a less discriminating public. What began as a refinement of the music hall not infrequently turned into a music hall itself. Berlin’s Schall und Rauch (Noise and Smoke, a quotation from Goethe’s Faust), was founded by the director Max Reinhardt as a haunt for theatre people that specialised in parody. It soon turned into a platform for the experimental staging of classics and new plays. Revived in larger premises and dominated by DADAists, it failed to fill seats and ended as an ordinary beer hall offering incidental entertainment.

‘Dancing on a volcano’ is the standard phrase to sum up reckless insouciance on the eve of catastrophe. In the case of the Great War, it was the aftermath of the cataclysm that fostered ‘anything goes’ attitude. The most extreme of the avant-gardists had welcomed the war as a liberating force, the logical culmination of the inequities and idiocies of society. Safe in neutral Zurich, the DADAists felt free to assail gallery audiences with high-minded nonsense. After the war, their irreverence and high spirits spilled over borders to infect stages across Europe.

Official censorship had greatly hampered the pre-war cabaret from making frontal attacks on the establishment, keeping its influence peripheral. The earliest German cabarets had never reached a wide public and were limited in appeal. The Great War changed all that. The collapse of the Hohenzollern, Hapsburg and Romanov regimes permitted, at least at first, a broad latitude of expression in the performing arts. Long dammed-up protest and dissent spilt over into a cataract of political satire. The excitement of what was happening in the streets began to be mirrored on the cabaret stage not as abstract opposition but as specific and circumstantial criticism.

Cabaret Dance

The overthrow of the Kaiser, the revolutionary outburst that resulted in the establishment of a Social-Democratic republic, and the hardships of the inflation period were the troubled waters in which cabaretists could fish with success. Referring to the period directly following the Armistice, George Grosz wrote

The times were certainly out of joint. All moral restraints seemed to have melted away. A flood of vice, pornography and prostitution swept the entire country. ‘Je m’en fous’ was what everyone thought. ‘It’s time we had a bit of fun’.[3]

Berlin became a maelstrom, sucking in the energies and talents of the rest of the German-speaking world, what Stefan Zweig called ‘the Babel of the world… [a veritable] witch’s Sabbath, for the Germans brought to perversion all their vehemence and love of system…’[4] (Bear in mind that Zweig, a Viennese Jew, entertained a low opinion of the average German). The breakdown of values communicated a dementia to those middle-class circles that had prided themselves on their sense of order. The examples of Berlin and Munich were so influential that within a few years the revolutionary transformation of the mental and artistic habits of the Germans was complete. They were eager for color, disarray and untrammeled performance.

One outlet of release was the dance craze. Dance halls proliferated: tangos, fox-trots, one-steps, shimmies and Bostons were introduced weekly; and the frenzy of the inflation period worked itself out in complicated steps imported from America. One private citizen, driven frantic by the fluctuations between civil war and everlasting carnival, plastered the advertising kiosks with a poster reading ‘Berlin, your dance is death’.[5]

Berlin’s dance was also nude. Isadora Duncan’s scandalous bare feet had quickly been outdone by exhibitions of the whole undraped human body in motion. The factors that contributed to Nakttanz included reaction against the prudery of the Wilhelmine era and a discharge of tension amidst wartime depression and postwar anxiety. Certain progressive groups sponsored nudism as a healthy way of life; others vaunted voyeurism as a legitimate hobby of the modern city dweller. The performers themselves protested that a beautiful female torso was itself a work of art worthy of contemplation. And, finally, at a time when maimed war veterans were to be seen begging on every street corner and prostitution throve as an economic necessity, the body objectified was regarded as a fit (in both senses) medium of entertainment.[6]

The naked dance, first performed as chaste evenings of beauty by Olga Desmond in 1909, and then persecuted by the police before the war,[7] was re-introduced after the German revolution by Celly de Rheidt (Cäcilia Funk, b.1889), mistress of an ex-army officer who pimped for her performances. The artistic pretensions of her recitals at the Berlin Chat Noir were pure kitsch, but taking the cue from her, almost every cabaret and nightclub featured unclad dance, often with Salome as a pretext. (One such Salome appeared at the White Mouse, where the guests wore masks). The censors’ annoyance became outrage when nudity was enhanced by a sado-masochistic theme, as in the whip-dance called ‘A Night of Love in the Harem’.

Olga Desmond performing the ‘Sword Dance’ (1908). Photo by Otto Skowranek.

The most sensational nude dancer of the time was Anita Berber (1899-1929), whose life and creations – Horror, Vice, Depravity, Ecstasy, and Cocaine (1922-25) – incarnated the younger generation’s thirst for uninhibited experience. Berber was a glamor queen who appeared in silent films and modeled for painters and porcelain makers, a lesbian who set the fashion by appearing in public in a tuxedo and monocle, a media celebrity who hung out with bicycle racers and boxers. Her dance partner and second husband, Sebastian Droste (Willy Knoblauch, 1898-1927), who had worked with Celly de Rheidt, introduced her to cocaine. He succumbed to it; she declined under its influence and died impoverished at the age of thirty.

What is curious about the much-touted ‘decadence’ of Berber and Droste is its retrospective aspect. Although ‘decadent’ had been a slur flung by Nietzsche at Wagner and by reactionaries at Wedekind and Stefan George, Wilhelmine Germany had not been much roiled by the doctrinaire decadence of the Mauve Decade. If it had, sophisticates might have found these performances jejune and déja vu. In photographs and posters, the couple resemble figures out of Aubrey Beardsley, plucking their way through Baudelaire’s Fleurs de mal (1857). Droste’s scenario for KOKAIN (COCAINE, 1922) seems a telegraphic resumé of the poems of Verlaine and Ernest Dowson:

Schwälende Lampe

Tanzender Schatten…

Was will dieser Schatten

Kokain

Aufschrei

Tiere

Blut

Alkohol

Schmerzen

Viele Schmerzen[8]

[Lamp smoldering/Shadow dancing…/What does this shadow want/Cocaine/Scream/Beasts/Blood/Alcohol/Pain/Much pain]

And so on. All this was interpreted physically by protracted arabesques, slow motion and backward head movements in service of a ‘dynamic of dreams’.[9] Yet the choreographic femme fatale, personified by Maud Allan and Gertrude Hoffman in the prewar Salome craze, reeling and writhing in Orientalist frenzy over the head of Iokanaan, had already become a hackneyed fixture of the variety stage. Friedrich Holländer later teased the fad for stage nudity in his song ‘Zieh dich, Petronella!’ (‘Take It Off, Petronella!’)

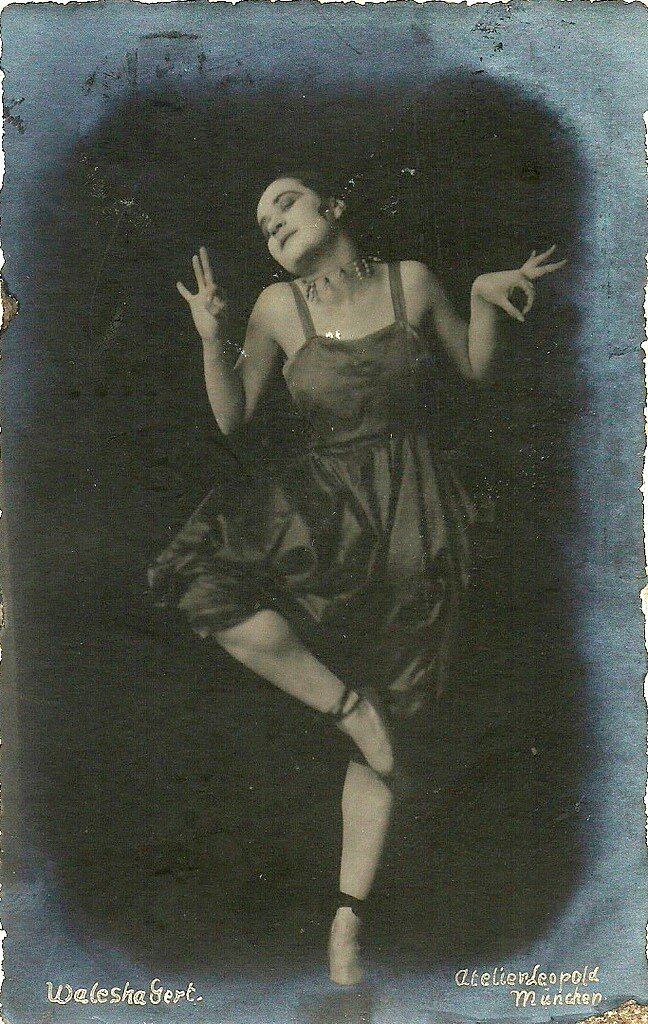

Valeska Gert, Dance in Orange, Munich (1918).

Far more innovative were the dance-pantomimes of Valeska Gert (Gertrud Samosch, 1892-1978). She told of hearing a ‘scrawny girl’ at the Romanesque Café declare, ‘We want the “outlandish” in dance’, so she set out to accommodate the request. ‘Because I didn’t like solid citizens, I danced those whom they despised – whores, procuresses, down-and-outers, and degenerates’. [10] She claimed to be the first to put a streetwalker into a dance-pantomime, Canaille. The act included a mimed orgasm and its aftermath. ‘I was dancing coitus, but I “alienated” it’. Other impersonations included a lecherous but impotent bawd, a woman giving birth, and another dying. Gert’s kinetic enactments of sex and death differed from Berber’s because they were unromantic and impassionate; her world was the cityscape of George Grosz, cruel, uncaring and up-to-date. Even Gert, however, was building on an earlier tradition, that of the apache dance, in which a Parisian pimp in cap and cummerbund would brutalise his female meal ticket, flinging her about and pulling her hair. Originally a novelty in French revue, it became a popular sensation in nightclubs and vaudeville, losing along the way its origins in fin de siècle chanson réaliste. No one complained as they did about nudity; the abuse was even glorified in torch songs such as ‘Mon Homme’ (sung by Fanny Brice as ‘My Man’).

The Kabarett

Kurt Tucholsky (1890-1935), the great oppositional columnist and poet, drew a sharp distinction between cabaret and what he called Kabarett. Cabaret’s prime function is to entertain. The Kit Kat Klub Sally Bowles performs in is the kind of ‘amusement cabaret’ (Vergnügungsstätte) that politically-engaged artists looked down on. Its high end was represented by the elegant, Ziegfeld-style revues mounted by the dancer-impresario Erik Charrell;[11] the down-market end was a kind of glorified Tingel-Tangel. For Tucholsky, Kabarett had a duty to maintain an adversarial stance in order to change society. ‘Nothing is harder and takes more character than to stand in open opposition to one’s time and loudly say “No!”’[12] In his view, there were no bounds to satire, whose writ ran to everything under the sun.

Despite Tucholsky’s preference, the average Weimar cabaret was far from programmatic in its artistic or socio-political aims. As it developed from underground, coterie or avant-garde to a genuinely popular entertainment, content – and, to a lesser degree, form – was dictated by the public. The instability of their lives led them to prefer humor that was glancing and sarcastic. The more embroiled the political situation became, the lighter the diversions offered by the cabaret.

While left-wing cabaret moved increasingly towards agitprop to counteract the rise of fascism, the run-of-the-mill cabaret preferred witty song-and-dance, tinged perhaps by liberal sympathies but by no means doctrinaire. This enabled a mass audience to feel au courant but basically unchallenged. The cabaret was omnivorous, shoveling in great portions of whatever was exciting and innovative – American jazz, dance novelties, cinematic and radio techniques – and regurgitated them, often in partially digested form. The ingestion of anything that proved attractive and alluring led many cabarets to adopt a revue format. And gradually censorship resumed, via libel suits instigated by private individuals, obscenity prosecutions by state’s attorneys, and harassment by right-wing factions. A cynic might say that the cabaret’s decadence lay in its decline from literary experimentation to ‘professional’ slickness.

By the mid-1920s every smart young thing affected a pose of ‘perversion’. As early as 1922 the song ‘Der Pornograph’ by Hans Natonek (1892-1963) had shown the hack who churns out 500 lines about loose women and sexual depravity to be a lower middle-class paterfamilias who needs an atmosphere of blue crepe paper and cheap perfume to jump-start his creativity.[13] A decade later Friedrich Hollaender (1896-1976), known for ‘Falling in Love Again’ (1930) and ‘Jonny’ (1931), spoofed the public desire to be thought perverse in ‘Starker Tobak’ (‘Shag Tobacco’, 1931) sung by wife Blandine Ebinger. It begins

Ich bin ja so durchaus verlastert,

Ich bin ja so furchtbar verrucht,

Est gibt ja für mich nichts mehr Neues,

Ich hab ja schon alle versucht.

[I am so completely vice-ridden,

So crazily avid for fun!

I’ve tried all the thrills that are hidden,

There’s nothing new under the sun].[14]

The verses enumerate these thrills: teething on opium, drinking molten tin and yoghurt laced with sulphur, eating raw meat and ground glass, having sex with wrestlers and mannish women.

Heut brauchen meine Nerven – neue Schärfen!...

Starker Tobak, starker Tobak, wilder Sinne gieriger Fraß.

Ach was bin ich für ein per- für ein ganz perverses Aas!

[My nerves crave as satiation new sensations…

Shag tobacco, shag tobacco, wild excitement, heady wine!

Ah, I’m what you’d call a per- a perverted filthy swine!]

The search for ever greater stimulus becomes increasingly surreal and eventually counterproductive, eventuating in listening to recordings of Bach and having conjugal sex. The song’s original ending went:

And lösch das schwule Ampellicht.

And hör im Traum wie Goebbels spricht:

‘Ei, wie rollt das Köpfchen!’ – Was?

[Dim the sultry lamp o’erhead,

And hear in dreams what Goebbels said:

‘Some heads are going to roll’. – What?]

This forecast of the Nazi takeover was censored and never performed; a more anodyne set of lines was substituted. That same year Holländer created a variant, ‘Die Kleptomanin’ [‘The Kleptomaniac’], whose persona is a woman insanely addicted to stealing worthless items (Dreck).

Despite the growing attendance at cabaret by a general public, its personnel and creators continued to be drawn from fringe groups that shared an ironic point of view. The proliferation of cabarets allowed minority concerns to infiltrate popular entertainment. Throughout central and eastern Europe, a predominant proportion of performers, composers, authors and impresarios were Jews; German-language cabaret was permeated with Yiddish rhythms, inflections and attitudes. Urban theatre-goers also contained a high percentage of Jewish patrons, although the bourgeois, like their gentile counterparts, preferred operetta and revue with cabaret attracting intellectuals and the politically engaged.

Weimar Berlin boasted the most conspicuous and lively homosexual subculture in Europe. (I use ‘homosexual’ advisedly since that was the standard term at the time, whereas ‘gay’ or ‘queer’ are anachronistic). In 1919 Dr Magnus Hirschfeld founded an Institute for Sexual Science, intending to study sexual variation and to militate against §175, the legal statute condemning sex between men. Known as the ‘blackmailer’s charter’, it remained in force under the Weimar republic, but was often a dead letter in the face of everyday practice. Male prostitution was as blatant as the female variety. (The rumor ran that if one asked a policeman to direct one to a brothel, he would inquire which sex one would prefer).

In the world of cabaret, not only were many public favorites open about their amatory preferences but homosexual resorts became must-sees on the itinerary of every urban tourist. By the late 1920s, a saunter through the same-sex clubs and bars was a standard item on the sightseer’s itinerary, offered even by Cook’s Tours. This was particularly the case with such classy transvestite bars as Eldorado and the Mikado.[15] The exchange of genders might provoke confusion rather than outrage in the casual visitor, as was the case with the composer Ralph Benatzky.[16] Growing familiarity with unorthodox sexualities seen in their (un)natural habitats promoted a change in public opinion, not full acceptance but a kind of bemused tolerance. However, it is noteworthy that even a 1931 Führer durch den ‘lasterhafte’ Berlin (Guide to ‘Wicked’ Berlin) should find it necessary to put scare quotes around ‘wicked’, suggesting the artificiality of the vice on display.[17]

The Eldorado club, Motzstraße, Berlin (1932).

A few of these clubs housed their own cabarets. The Kabarett die Spinne (the Spider), for instance, offered such weekend attractions as Luziana the Enigmatic Wonder of the Globe – man or woman? – and a male twin song-and-dance act. The Kurfürsten-Kasino featured the female impersonator Micke parodying Ruth St Denis and other famous dancers. The cynosure of the subculture was the Alexander-Palais (later Alexander-Palast) with its huge ballrooms, orchestra and first-class cabaret.[18]

At the down-market end were such dives as ‘The Mud-hole’, described by Klaus Mann, Thomas’s son, in his quasi-autobiographical novel Der fromme Tanz (The Pious Dance, 1926). His hero, the effete and impecunious Andreas, stranded in the big city, goes on stage to present ‘a couple of spicy bagatelles’. Wearing a red neckerchief as a Puppenjunge or toyboy, he sings ‘Our legs are pretty, oh so pretty,/Would you like to come our way?/We’re so alone – ‘tis pity/--All through the livelong day’. In the next sketch he comes on as a sailor with a painted face in a bacchanalian apache duo.[19] This is playing at decadence, to provide the jaded on-lookers a cheap thrill.

Most of these rendezvous were, in fact, similar to the one described by Isherwood: modest bar-rooms with tiny dance-floors and the occasional offering of a song to piano accompaniment. ‘Nothing could have looked less decadent than the Cosy Corner’. [20] The ambience was more that of a neighborhood pub than a palace of sin. It was pointed out to the visitor that many of the boys were ‘hetero’ and simply enhancing their incomes by sex trafficking. True decadence thrives on affluence; practices born of poverty and indigence deserve another label.

Lesbian clubs were slightly more exclusive. At the Pyramide in Berlin’s West End, one had to go through three doors before arriving at the ‘clandestine Eldorado of Women’.[21] Visiting artists and society women came to strike up an acquaintance with the city’s seamy side. The club’s anthem was the so-called Lila-Lied or Lavender Song. Lavender equates to the English pink or the Russian goluboj (light blue) as the homosexual color, because of its muted, in-between nature. ‘Lilac Nights’ alluded to the round of same-sex pleasure to be had in Berlin. The song of 1920 with music by Mischa Spoliansky (1898-1985), under a pseudonym, and words by Kurt Schwabach (Jacobson, 1898-1936) was dedicated to Dr Hirschfeld and considered a Bundeslied or anthem.[22] Its lines ‘We are different from the others’ (anders als die andern), drawn from Bill Forster’s 1904 novel of that name and the reform-minded silent film suppressed by the authorities, became a rallying cry. Gussy Holl sang it before a mixed audience at the KadeKo (Kabarett der Komiker) when it brought the house down.

The refrain, set to a march tempo, goes:

Wir sind nun einmal anders als die Andern

die nur im Gleichschritt der Moral geliebt,

neugierig erst durch tausend Wunder wandern.

und für die’s doch nur das Banale gibt.

Wir aber wissen nicht, wie das Gefühl is,

denn wir sind alle and’rer Welten Kind,

wir lieben nur die lila Nacht, die schwül ist,

weil wir ja anders als die Andern sind.

[After all, we’re different from the others

Who only love in lockstep with morality,

Who wander blinkered through a world of wonders,

And find their fun in nothing but banality.

We don’t know what it is to feel that way,

In our own world we’re sisters and we’re brothers:

We love the night, so lavender, so gay,

For, after all, we’re different from the others!]

Wilhelm Bendow (1884-1850) worked in a number of Berlin cabarets, including his own, Tü-Tü (both ballet skirt and an equivocal appellation), and Bendow’s Bunte Bühne (Motley Stage), transferring in 1934 to the KadeKo. Affectionately nicknamed ‘Lieschen’, Bendow assumed the stage persona of an outrageous and scatterbrained ‘fairy’, whose naïve questions punctured officialese or lent obscene connotations to flowery euphemisms. In this he resembled the ‘nance’ or ‘fairy’ comedians popular in American burlesque at the time: effeminate, unworldly, unthreatening. Bendow sang the Lila Lied in a lavender tuxedo before a lavender bar, but occasionally performed in drag, as in his monologue The Tattooed Lady: ‘Here on my breast is the political portion of my art gallery. Here I have all the Impotentates of Europe… (Points to her belly). Here I have the Reich’s automatic justice machine. You put in the defendant up at the top, and five minutes later a ready-made judicial murder comes out through the bottom… On my left rear upper thigh I have the German war heroes… on my right rear upper thigh I have the decline of the West’.[23]

Claire Waldoff (Clara Wortmann, 1884-1957), a regular at the lesbian clubs, emitted the allure of a ‘tomboy’.[24] Short and stubby, with a henna-dyed page-boy haircut and a hoarse voice, she would, however, sing of such male sweethearts as the ham-fisted bruisers ‘Hermann’ and ‘Wladimir’. Although some of her numbers had a feminist tinge (‘Raus mit’n Männer aus’m Reichstag’ [‘Kick the Men Out of Parliament’], ‘Ach Jott, wat sind die Männer dumm’ [‘Lordy but Men Are Dopes’]), they are uncharacteristic of her repertoire as a whole. She was considered the theatrical equivalent of Heinrich Zille, the cartoonist of the Berlin slums, delineating a rough-and-ready ambience of whores and derelicts. ‘Das war sein Milljö’ [‘That was his milyoo’][25] Waldoff sang in his honor, and it was hers as well. Again, this hearkens back to the chansons réalistes of French cabaret of the antebellum period.

Claire Waldoff at the Linden Cabaret, Berlin. Poster by Jo Steiner (1912).

A clear sign that the more daring features of cabaret performance could be made acceptable to a middle-brow public was their adaptation and adoption by the spectacular revue and the musical comedy. Bendow and Waldoff made frequent appearances in such shows, the former often as a running gag, the latter in Zilla-inspired sketches. The lesbian theme was domesticated by Schiffer’s revue number ‘Wenn die beste Freundin’ (‘When the best girl-friend’, 1928), a trio of wife, her intimate female chum and her husband (Marlene Dietrich created the role of the third wheel). However, much of this was a ‘masquerade of perversion’, contrived to compete with Paris in the matter of heterosexual display. The opulent exhibitions of naked female pulchritude promoted by Charell, Hermann Haller and James Klein were different only in opulence and numbers from similar commercial ventures at the Folies Bergère or even Minsky’s Burlesque in New York. When Klein included a caricatural sketch of a homosexual club in his revue Streng verboten (Strictly Forbidden), members of the Union of Human Rights protested and the homophile press denounced such defamation.[26]

The question of decadence is thus a question of viewpoint. Conservative, reactionary, bourgeois thinkers found the infiltration of an entertainment form by such alleged outsiders, and such signs of emancipation, to be a token of decadence. The burgeoning right-wing factions certainly thought so.[27] For the outliers themselves, public performance was a welcome liberation, healthy and beneficial.

The Nazis

Cabaret’s first impulse was to treat the Nazis as laughingstocks: the Jewish tenor Max Hansen, in the character of a Herr Kohn addressing Hitler, warbled ‘War’n Sie schon mal verliebt in mich?’ (‘Were you ever in love with me?’). The seizure of power in 1933 could not be laughed off. The most forceful cabaretists were politically to the left or Jewish or homosexual or all of the above. Immediately many of the more prominent figures in German cabaret emigrated, first to German-speaking countries such as Austria and Switzerland, and then, as the Reich’s depredations spread, to France, Holland, England and the Americas. Of the Berlin cabarets, only the Katakombe, the Tingeltangel Theater and the KadeKo (Kabarett der Komiker) carried on.

Kabarett der Komiker (December 1935). Photo by Willy Pragher. Staatsarchiv Freiburg.

The National Socialist press protested more and more loudly against ‘artists’ license to be fools’, ‘mockery by Jewish intellectuals’, even against allusions to proscribed performers. Claire Waldoff was forbidden to appear on stage and retired to provincial obscurity. Bendow’s silliness preserved his popularity with the Nazis until 1944, when a remark deemed to be politically offensive caused him to spend the last months of the war in a labor camp. The Katakombe and the Tingeltangel were shuttered in 1935, after the arrest of the former’s conférencier. Four years later, the only survivor, the KadeKo, run by the Munich raconteur Adolph Gondrell (1902-1954), was closed by Goebbels and bombed out in 1944.

The upshot was an official decree in 1941 from the Ministry of Propaganda, forbidding any performance by conférenciers. Goebbels complained of the mischief made by covert criticism of the Reich leadership and its policies, particularly in wartime. He alleged that it undermined national unity by its attacks on ‘our people’s unique race’. Most fundamentally, he condemned it as ‘a form of public entertainment engendered by a liberal-democratic style of government’.[28] This constituted a death sentence for cabarets carried out over the next four years.

It is worth noting that Goebbels’ diktat at no point accuses the cabaret of being dekadent. The most popular historical work of the Weimar period, Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West (1918-23), rejected the very notion of degeneracy, seeing the dissolution of democracies as a natural stage in the devolution of civilisation. Spengler was no Nazi, but his book’s anti-democratic tone and its identification of Jews as elements in this disintegrative process were congenial to fascist ideology. The popularity of Spengler’s thesis was, of course, lampooned by the cabaret itself. The conférencier Hans Reimann’s (1889-1971) ‘Der Untergang des Abendlandes’ (1923) is a dizzying catalogue of brand names, celebrities, and headlines, ending up ‘Das Abendland geht unter – letzter Trick!/Totschick! Mit Musik!’ (‘The West is going under – last trick!/Dead chic! Set to music!’).[29]

The concept that Weimar cabaret was ‘decadent’ involves a confusion with ‘degeneracy’, Entartung. The concept knits together several anti-modernist strands conspicuous at the fin de siècle and immediately afterwards. Max Nordau’s homonymous study of 1892 had characterised much of nineteenth-century creative achievement as degenerate, employing a term originally used to analyse criminal behavior. Tolstoy went even further in What Is Art? (1897), condemning art in general as a distraction from and a perversion of Christian values. Kaiser Wilhelm set the tone for his society in dismissing ‘modern art’ as anarchistic and anti-German; he also hated Berlin as a nursery for such subversive media. This sentiment survived his deposition. In the wake of the Russian Revolution, Nazi ideologues launched the slur ‘Cultural Bolshevism’, a transparent veil for anti-Semitism, Eager to make art an instrument of policy, the National Socialist Party adopted Entartung (degeneracy) as a blanket term for efforts to contaminate the wholesome Aryan aesthetic tradition. The roots of this tradition were to be found in the classical Graeco-Roman past, devoid of any possible Semitic contamination.

In 1937, the equation of degeneracy with the creative avant-garde was institutionalised by the widely-travelled Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition. An analogous display of Entartete Musik was staged in Düsseldorf in 1938 by Hans Severus Ziegler, both a Nazi official and an active homosexual.[30] Such expositions were aimed at orchestral music, but bans and critical denigration embraced the jazz-inflected melodies and Jewish composers of the cabaret. Particular opprobrium was cast on music said to be influenced by the African-American performers who had begun to appear on Berlin stages in 1926. When Josephine Baker had arrived from Paris she had been lauded as the embodiment of the present, of expressionism, of the primitive. The press insisted on the ‘negroid’ ‘nerve quickening music’, the raw rhythms, the body in constant motion, not always approving but clearly fascinated.[31] The Nazis conflated such imports with native Jewish compositions; this pairing constituted for them a blatant instance of counter-Aryan culture.

It seems ironic that the brush used by the Nazis to tar the cabaret would be wielded to glorify it by its later admirers. ‘Decadence’ is appealing to contemporary taste, but its application to Weimar cabaret is misplaced. While the cabaret’s antinomian stance suits modern art’s preference for the unconventional, provocative and oppositional, it cannot easily be reconciled with the morbid courtship of death and dissolution that the accepted fin-de-siècle concept of Decadence embraced.

Weimar cabaret vigorously and courageously engaged with its own times, commenting on every aspect of urban life, except, possibly, religion. In many ways it was more up-to-date, less precious than its prewar antecedents. Even when it was addressing a coterie, it had the advancement of that coterie’s interest in mind. Its outlook was cosmopolitan (which both Nazis and Stalinists considered Jewish) and sophisticated.

The Musical

Those fugitives who attempted to perpetuate cabaret performances outside the Third Reich cannot be thought to have disseminated decadence abroad. Erika Mann’s Pfeffermühle (Peppermill) carried on attacking Hitler in Switzerland, where it was brutalised and banned, and in New York, where it was ignored. Valeska Gert also tried New York, with her Beggar’s Bar in Greenwich Village and Provincetown, but its offerings were amateurish. Police prosecution came from licensing problems and non-payment of bills rather than subject matter or performance style.

Over the following decades, the English-speaking general public gave little thought to Weimar Germany, until the rediscovery of Bertolt Brecht in the late 1950s thanks to proselytisers for Brecht such as Eric Bentley, John Willett and Martin Esslin; the successful off-Broadway production of The Threepenny Opera (1928) in Marc Blitzstein‘s bowdlerised version; and George Tabori’s revue Brecht on Brecht. The last two featured Kurt Weill’s widow Lotte Lenya as a kind of guarantee of period authenticity. However, it was not until Kander and Ebb’s musical Cabaret that the Nazi defamation of the cabaret received a glossy make-over.

The seeds barely exist in the source material. Christopher Isherwood’s story collections Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935) and Good-bye to Berlin (1939) are reticent on the matter of perversion. The latter does feature the ‘divinely decadent’ Sally Bowles, with her chalk-white face, green finger-nails and insouciant promiscuity. Sally, however, is an expatriate, more an offshoot of the Bright Young Things than part of the German Lost Generation. Discreet allusions to homosexuality are projected on to a few characters, while the narrator remains abstinent. John Van Druten’s stage adaptation I Am a Camera (1952) diluted this even more, while its film version suffered from a dual censorship, British pre-production and American post-production. Julie Harris in both cases turned Sally into a waif reminiscent of her Frankie in Member of the Wedding (1950).

When the creative team of Joe Masteroff for libretto, John Kander for music and Fred Ebb for lyrics came to transmute this material into a musical for Broadway, they abjured drawing on Isherwood directly, instead adapting Van Druten’s adaptations. The book conventionally centered the interest on two doomed love stories: that of an American writer Cliff Bradshaw for the English performer Sally Bowles; and that of a Jewish fruiterer for a Berlin landlady. It was the director Harold Prince who wanted to make Weimar stand in for a turbulent US and replace narrative with expressive metaphor. It was he who introduced the structural device of interpolated cabaret numbers to provide ‘Brechtian’ distance. The theatre audience of 1966 was reflected in a tilted mirror and various cinematic techniques were employed to create a simulacrum of ‘expressionism’. Kander claimed that he avoided listening to Kurt Weill’s music as he wrote the score, though he immersed himself in popular German tunes of the period. Nevertheless, as a token of authenticity, Lotte Lenya was cast as the landlady. Lenya remarked that the Kit Kat Klub was unlike what she recalled of 1920s cabarets, lacking as it does the satiric and political aspects.[32]

Still, the sensitivity of the typical Broadway playgoer is respected; the cabaret numbers, though cynical, tend to be upbeat, naughty rather than provocative, and the innuendo never becomes graphic. Sally’s abortion is conveyed obliquely, and she suffers no serious mental breakdown. Despite opening night walk-outs (reversed once the reviews appeared), confrontation was low-key and the discomfort level low. True decadence is kept offstage. For the screen version in 1972, with the glamorous Lisa Minnelli as Sally and the dashing Michael York as Cliff, Bob Fosse reversed the nationality of the protagonists, half-heartedly hinted that they were bisexual, and foregrounded the Nazi threat. By relegating all song and dance to the cabaret episodes, Fosse made them garish displays of showbiz knowhow rather than the kind of social commentary Goebbels had found objectionable.

However, these darker shadows eclipsed the earlier Broadway avatar in the public memory. The liberties taken by Fosse gave license for what one journalist calls ‘the progressive outing of the leading man’[33] as Cliff moved from bisexual to openly gay. Another factor conducive to the enhanced ‘decadence’ of the musical was the publication in 1976 of Isherwood’s Christopher and His Kind, a more candid account of his time in Berlin. It emphasised his incursion in the hustler subculture and the deleterious effect of the Nazi incursion on those he knew. The book was widely covered, quoted and paraphrased in the press, which invariably cited the line ‘For Christopher, Berlin meant boys’.[34] Elements of that reality began to creep into directorial rethinking.

Cliff and Sally are outsiders, for whom Berlin is a Petri dish in which their potential for vice might be cultivated. The chief conveyor of decadence in Kander and Ebb’s musical is a wholly invented figure, the Emcee. In the original production and in the film, Joel Grey incarnated an unnervingly mercurial host, now Puckish, now Mephistophilian, an imp who turns into a presiding devil. As lord of misrule, he stands for the heedless hedonism that corrupts society. It is implied rather than stated that his increasingly amoral antics symbolise Hitler’s ascension to power.

None of this relates to the actual practice of Berlin cabarets. The Parisian cabarets had adopted from the year-end revue the compère or commère who addressed the audience directly, set the tone, introduced and explicated the numbers, and generally held the evening together. The conférencier (the term comes from the naturalist theatre) conferred not only a clear identity on a cabaret, but enhanced the sense of irony indigenous to the form. His (occasionally her) commentary allowed the spectators emotional distance from the phenomena under scrutiny. In Weimar Berlin such a master of ceremonies might bestow a sharp profile on a cabaret, but was seldom aggressive or grotesque.

The most epicene of these, Paul Schneider-Duncker (1878-1956), famous for his impersonation of Berlin shopgirls, dressed in elegant evening wear; his polished manner resembled that of Noël Coward. More characteristic were the popular conférenciers Fritz Grünbaum (1880-1941) and Werner Finck (1902-78). Grünbaum, a bespectacled, balding Viennese, came across as a put-upon everyman, who often appeared in duologue sketches. Finck, a star of the intimate Katakombe, wore baggy suits and scuffed shoes, and attacked his targets obliquely with evasive humor and innuendo. Both ridiculed the Nazis long after Hitler had come to power. Finck at the Katakombe teased the regime until 1935 when, as the result of a particularly daring sketch, the comedian was ‘transferred’ to Esterwegen concentration camp. Thanks to the intercession of the actress Käthe Dorsch, mistress of Hermann Goering, who was at the time on the outs with Propaganda Minister Goebbels, Finck and his colleagues were acquitted of offenses against the anti-libel law, despite considerable evidence against them. He was, however, banned from the stage. As a Jew Grünbaum was not so lucky; he would die of tuberculosis in Dachau.

The willful decadence of Cabaret’s Emcee was metastasised in the theatrical revival staged by Sam Mendes at the Donmar Warehouse in 1993 (and on Broadway five years later). By this time the Gay Liberation Movement and a host of plays and films about the Holocaust had helped inform the public’s opinion. Mendes, more interested in the rise of fascism than in sentimental romance, decided that stronger meat would be needed to point up Weimar decadence. Mendes’s Emcee was played by Alan Cumming as a jester out of a sado-masochist’s dungeon, with track marks down his arms, rouged nipples and torn hosiery. His every inflection and gesture could be read as sexual. His backchat with the audience was aggressive, intent on implicating them. Cross-dressing was blatant, and the Kit Kat Girls were supplemented by Kit Kat Boys, so that the number ‘Two Ladies’ became an exercise in pansexuality, a smuttier variant of Hollaender’s ‘Wenn die beste Freundin’. This Emcee’s detachment, revealed in the original staging only in the finale, was now given its own song, ‘I Don’t Care Much’, sung while Sally is undergoing her abortion. His personal disintegration is an emblem of Germany’s.

In the final tableau, against barrack-like silhouettes, to the mounting background rumble, the Emcee doffs his trench coat to reveal the striped pajamas of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen. He wears a yellow star of David and a pink triangle, identifying him as a Jewish homosexual. The last bow of Joel Grey’s Emcee had been an ironic farewell to the audience and a quick vanish into a blackout. This might be construed as the National Socialist darkness enfolding the world, thus equating ‘decadence’ with fascism. Cumming’s Emcee stared at the frozen company members, then at the audience, and bent convulsively, silently, before disappearing. This suggests that the Nazis were right, according to their world-view: the cabaret was decadent, a haven for aberrant, undesirable and un-German types, hence subversive and fit for extermination. The power of the concluding image occludes the ambivalence of the message.

Mendes’s radical rethinking of Cabaret has been copied in most subsequent revivals. Or else an attempt is made to ratchet up the decadence factor so that the musical becomes less a cautionary tale and more a horror show. This means that the distance between the actual Berlin cabarets of the 1920s and ‘30s and the musical’s latest directorial and design concepts wind up light years apart. The Shaw Festival staging of 2014, for example, was a phantasmagoria built around a gigantic spiral staircase bristling with jagged shards and ablaze with light bulbs, Metropolis meets Kristallnacht. This might have been a homage to the extravagant Haller revues of the Weimar period except that the Kit Kat girls and the hulking Emcee were played as galvanised zombies. Weimar was no longer a mirror image of the way we live now, nor was it a Grosz drawing come to life; it was some futuristic dystopia populated by mannequins. Decadence ceases to be when there is no normal standard of behavior against which to define it.

Professor Laurence Senelick is Fletcher Professor of Oratory Emeritus at Tufts University, and has published widely on cabaret, drag, popular entertainment, and Russian theatre. His most recent books include Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture (2017), and Soviet Theatre: A Documentary History (2014). He is the recipient of grants and awards from, among others, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the American Council of Learned Societies. He is also a widely-produced translator of plays from playwrights including Anton Chekhov, Jean Giraudoux and Ferdinand Bruckner.

Notes

[1] The literature on Berlin cabaret is voluminous. Some basic texts: In German, Heinz Greul, Bretter, die die Zeit bedeuten (Cologne: Koepenheuer & Witsch, 1967); Rainer Otto and Walter Rösler, Kabarettgeschichte (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1977); Klaus Budzinski, Pfeffer ins Getriebe. So ist und wurde das Kabarett (Düsseldorf: Universitas, 1982). In English, Peter Jelavich, Berlin Cabaret (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993); Laurence Senelick, Cabaret Performance: Europe 1890-1940, 2 vols. (New York: PAJ Press, 1989; Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993); Lisa Appignanesi, The Cabaret, 2nd ed. rev. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

[2] Detlev Peukert, Die Weimarer Republik. Krisisjahre des klassichen Modern (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1987), 87, 89. For a detailed account, see Magnus Hirschfeld et al., eds., Zwischen zwei Katastrophen (Sittengeschichte der Nachkriegszeit), 2nd revised ed. (Hanau am Main: Karl Schustek, 1966), esp. chapters 8, 11, 19-21.

[3] A Small Yes and a Big No. The autobiography of George Grosz, trans. Arnold J. Pomerans (London: Allison & Busby, 1982), 94.

[4] Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von Gestern. Erinerrungen eines Europäers in Gesammelte Werke, ed. K. Bech (Frankfurt: Fischer, 1982), 358.

[5] Hans Ostwald, Sittengeschichte der Inflation Ein Kulturdokument aus den Jahren des Marksturzes (Berlin: Neufeld & Henius, 1951). Friedrich Hollaender later wrote a tango with that title.

[6] It was said the Berlin police had 25,000 full-time professional prostitutes on its books, leaving aside part-timers and opportunistic sex workers for profit. David Clay Large, Berlin (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 180. However, prostitution driven by economic hardship cannot be stigmatized as licentiousness.

[7] Adorée Villany, Tanz-Reform und Pseudo-Moral, trans. Mirjam David (n.p., [Villany, 1913]).

[8] Sebastian Droste, KOKAIN, to music by Saint-Saëns, in Lothar Fischer, Anita Berber. Tanz zwischen Rausch und Tod 1918-1928 in Berlin (Berlin: Haude & Spener, 1984), 70-71. Unless otherwise noted all translations are my own.

[9] Joe Jenčik, ‘Versuch einer Analyse des Tanzes der Anita Berber’, Schrifttanz, 1 (1931): 10.

[10] Valeska Gert, Mein Weg (Leipzig: Devrient, 1931), 34.

[11] Kevin Clarke, ‘Im Rausch der Genüsse. Erik Charell und die entfesselte Revueoperette im Berlin der 1920er Jahre’, in Kevin Clarke, ed., Glitter and Be Gay. Die authentische Operette und ihre schwulen Verehrer (Hamburg: Männerschwarm, 2007), 108-39.

[12] Kurt Tucholsky, ‘Politische Satire’, Die Weltbühne (9 Oct. 1919).

[13] Hans Natonek, ‘Der Pornograph’, in Vom Untergang des Abendlandes. Kaberett-Texte der zwanziger Jahre, ed. Wolfgang U. Schütte (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1983), 16-17.

[14] Friedrich Hollaender, ‘Starker Tobak’, in Volker Kühn, ed., Kleinkunststücke Band 2 Hoppla, wir beben. Kabarett einer gewissen Republik 1918-1933 (Berlin: Quadriga, 1988), 165-66.

[15] For a negative contemporary description, see Peter Sachse, ‘Der verkehrte Ball im ‘Eldorado-Kasino’’, Berliner Journal 157 (1927): 2.

[16] Ralph Benatzky, Triumph und Tristesse: aus dem Tagebücher von 1919 bis 1946, ed. Inge Jens and Christiane Niklew (Berlin: Parthas, 2002).

[17] Its author Curt Moreck (Konrad Hämmerling) specialized in this sort of pot-boiler; his other works include sexual histories of the modern age, the cinema and women in art.

[18] For a detailed list, see Eldorado. Homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850-1950. Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur, ed. Michael Bollé (Berlin: Frölich & Kaufmann, 1984), 65.

[19] Klaus Mann, Der fromme Tanz (Berlin: Bruno Gmünder, 1982), 61; trans. as The Pious Dance by Laurence Senelick (New York: PAJ Publications, 1987), 64-67. Mann himself had suffered a humiliating audition at the swish cabaret Tü-Tü singing an Oscar Wilde tribute: ‘Perversion’s really swell, my boy/Perversion keeps you well, my boy’. Mann, Kind dieser Zeit (Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1983), 170.

[20] Christopher Isherwood, Christopher and his Kind (Los Angeles: Sylvester & Orphanos, 1976), 30. The model was Noster’s Restaurant zu Hütte.

[21] Claire Waldoff, Weeste noch…! Aus meinen Errinerungen (Düsseldorf/Munich: Progress-Verlag Johan Flauberg, 1953), 54-55. See Adele Meyer, ed., Lila Nächte. Die Damenklubs der Zwanziger Jahre (Cologne: Frauenbuchverlag, 1981).

[22] Spoliansky and Schwabach were heterosexual and Jewish. The former managed to escape Nazi persecution to pursue his career in London; the latter was murdered in the Łodz ghetto.

[23] Laurence Senelick, ‘The Good Gay Comic of Weimar Cabaret’, Theater (Yale) (Summer/Fall 1992): 70-75.

[24] Helga Bemmann’s otherwise detailed Wer schmeißt den da mit Lehm? Eine Claire-Waldoff Biographie (Berlin: Lied der Zeit, 1982) draws a discreet veil over her private life.

[25] ‘Das Lied vom Vater Zille’ by Walter Kollo and Hans Pflanzer, in Die Lieder der Claire Waldoff, ed. Helga Bemmann (Berlin: Arani/Eulenspiegel, 1983), 74-75.

[26] ‘Demonstration des Homosexuellen! Skandalscene in der Komischer Oper!’, Das Freundschaftsblatt (8 July 1923): 1. Thanks to Kevin Clarke for providing me with this article.

[27] An essay ‘Die Welt wird Nackt’ (‘The World Strips Off’) by Charell in the programme to his revue Von Mund zu Mund (Mouth to Mouth, 1927), with Bendow, Waldoff and Dietrich in the cast, was interpreted this way by right-wing reviewers.

[28] Joseph Goebbels, Anordung betreffend Verbot des Confèrence- und Ansagewesens (1941), trans. in Senelick, Cabaret Performance, II, 281-82.

[29] In Vom Untergang des Abendlandes, 19-21.

[30] Albrecht Dümling and Peter Girth, eds. Entartete Musik. Dokumentation und Kommentar zur Düsseldorfer Ausstellung von 1938, 3rd rev. and enlarged ed. (Düsseldorf, 1993); Hans-Werner Heister, ed., ‘Entartete Musik’ 1938 – Weimar und die Ambivalenz (Saarbrücken: Pfau, 2001).

[31] For two differing views, see Alfred Polgar, ‘Chocolate Kiddies’, Die Weltbühne, 6 (1926), 224, and ‘Erste Negerrevue in Berlin’, Vossische Zeitung (6 June 1926). For a typical Nazi attack on the ‘morbid’ and ‘maimed’ musical scene in Germany prior to 1933, which was to be ‘healed’ and ‘wholesome’ under the new regime, see Unsterblicher Wälzer (Immortal Waltzes, 1940) by the SS Officer and composer Fritz Klingenbeck.

[32] This musical has been exhaustively researched and analyzed. See, inter alia, Keith Garebian, The Making of Cabaret, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); Linda Sunshine, ed., Cabaret: The Illustrated Book and Lyrics (New York: Newmarket Presss, 1999); and Barbara Wallace Grossman, ‘“Pained Laughter”: Cabaret, The People in the Picture, and the Paradox of Holocaust Musicals’, in Holocaust Theater and the Legacy of George Tabori, ed. Martin Kagel and David Saltz (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021). My thanks to Prof. Grossman for allowing me an advance look at her essay.

[33] Margaret Gray, ‘50 Years of Cabaret’, Los Angeles Times (20 July 2016).

[34] For a useful survey, though based wholly on English-language sources, see Zoe C. Howard, ‘“Berlin Meant Boys”: Christopher Isherwood in Weimar Germany’s Gay Berlin’, Onyx Review 2, 1 (2016): 15-23.